Nostalgia, Fashion, Taste and Style

Part 2 - The Art of Performing Vintage and the Authenticity of Nostalgia

This series is based on a Capstone thesis exploring the various facets of Vintage as a concept and its most scandalous affair with the fashion and media industries, one that’s unfolding in coincidence with a period of great uncertainty and change. The author breaks down several key theories and phenomena to get to the bottom of Retromania and identify its key players, practices, and consequences in contemporary popular culture.

“Nostalgia has ‘an amazing capacity for remembering sensations, tastes, sounds, smells, the minutiae and trivia of the lost paradise that those who remained home never noticed’”

Nostalgia

Nostalgia is a feeling we’re familiar with. It’s a sense that’s stimulated so often we hardly notice it anymore. The word has many meanings today that deserve to be discussed before looking at the impact and role of nostalgia in contemporary pop culture.

Your childhood bedroom (or that of your older sister, her best friend, your cousin, your sister's best friend's cousin...)

One of the first academic uses of the term comes from Johannes Hofer, a Swiss physician, who, way back in 1688, defined nostalgia as a pathology. It was metaphysical ailment likened to an extreme form of homesickness - not just the desire to return to a familiar space, but also the yearning for a familiar time (Leone 9). Nostalgia lives in the senses, recalling the “sensations, tastes, sounds, smells, the minutiae, and trivia of the lost paradise that those who remained home never noticed” (Jenß 113). This definition (however whimsical and/or intangible) might explain why many, especially from past generations, wouldn’t get the frenzy surrounding vintage objects. They’re blind to the nuanced value given to garments and items they consider to be just “old.” They were the ones who “remained home,” taking for granted the mundanities (what we might consider charming simplicities) of a time past. However, Hofer’s theory doesn’t even begin to explain why “temporal tourists,” namely from generations too young to remember or even exist in that same past, long for a space and time that they never actually called home (Leone 10).

Ersatz nostalgia, also known as “imagined nostalgia,” is arguably what we encounter most often today as contemporary trends (and of course, brands) are trying harder than ever to tap into the temporal market. For reference, “Ersatz”means that anything is a substitution for the real deal. Ersatz objects are inferior to their truer counterparts, and this description is typically used in the context of consumption when discussing products or reproductions. According to Arjun Appadurai, “[t]his kind of nostalgia…does not generate a connection with one’s own lived and memories experience of the past, but rather fosters a feeling of desire or longing for an imagined past – one that can be directly translated or channelled into consumer desires” (qtd. In Jenss 112). There is a reason that “throwback collections” and nostalgic reproductions see so much success in the market – older consumers are taken back to when they used that product in a simpler past, and younger consumers wish they could have been around to appreciate the products of the past, as they seem simpler and more wholesome than what’s on today’s market. The true muscle behind retromania is, beyond question, the latest generation of consumers and internet users, sometimes known as Gen Z. These are people born after 1995 with a ton of buying power and even more influence on consumer behaviour (Torossian, 2020; Hoffower and Kiersz, 2021). The only past that they (I guess I should say we) know isn’t too far away. So does that mean that motivations of this generation’s nostalgic feelings are primarily consumptive and not at all based in real nostalgia?

Then: choosing Nike for this futuristic (then-fictional) accessory sets up the brand for nostalgic marketing opportunities for decades to come

Now: 2016 release of the Nike MAG created a huge buzz amongst sneakerheads and BTTF fans alike - despite their price tag

It is difficult to detach discussions of nostalgia from the connotations of consumption and consumer culture, as the two concepts are now so tightly linked.

There seems to be a battle between obsession with the past and finding sanctuary in it. Today the symptoms of nostalgia craft an imagined and idealized version of the past which carries feelings of “serenity compared to the present experience” (Leone 9). This is to say that the process of summoning memories is selective – we construct place, time, and culture collectively; re-writing and “renegotiate[ing]” the past in a way that’s not just palatable but also comforting. This “fashioned” collective consciousness sterilises the past, picking and choosing elements from a given era to construct a utopian - and in most cases highly marketable – notion of a past worth escaping to (Bruggeman 319).

Consumer culture and Marketing

BK reimagines classic logo

To understand why and how nostalgia can be used so heavily (and with so much success) in contemporary marketing, we first need to understand the systems and conditions in place that nurture such trends. Malia Simon’s analysis of consumer preferences and the current consumerist landscape blames neoliberalism, “a breed of capitalism characterized by a “radically free market in which competition is maximized, free trade achieved through economic deregulation [and] privatization of public assets…and monetary and social policies [that favour] corporations” (Simon 22). Sound familiar? This is the system we are currently living under and attempting to understand this fickle beast while we’re still snuggled in its indulgent embrace is no easy feat. What differentiates neoliberal systems from past periods is the blurred line between character and consumption. Life moves so fast these days that the average consumer falls into what is called a “corroded character,” where identity is not fully developed due to the suggested pace of life. This lack of a strong identity means, as consumers, we seek fulfilment of identity in commercial spaces. “The buying and wearing of brands have become our way to belong, find our place, and lend coherence to our identities,” but the modern consumer’s dilemma is this: the conditions for consumption that are created by a mix of socio-economic systems under the Neoliberal era have led to a streamlined definition of personal style and even personality itself (Simon 2020).

Simon breaks down the characteristics of neoliberalism as they are seen in retail spaces, using as a case study “Vintage Lines” from stores like Urban Outfitters and Brandy Melville, which released a collection of “single copy” garments “manufactured to resemble that of thrift stores or smaller, boutique-like businesses,” creating an illusion for the consumer (although it’s more of a delusion, frankly). The illusion is that, by buying this or that item, the consumer is making a unique and conscious purchase, that “they won’t see themselves coming and going” wearing this garment – it’s one-of-a-kind. Big brands, not only in fashion, have begun to realise the appeal of second-hand shopping and thrift culture, and notice the death grip that nostalgia has on a generation lost amongst itself.

The neoliberal condition has us chasing a past life, where modes of production were more primitive, garments were manufactured on a smaller scale, when life seemed simpler, and maintaining a “sense of identity…was…more accessible” - or so it seems (Simon 22). Simon argues that “the popularity of the vintage trend is not merely a result of our mourning for the past, but also a suggestion that we’re challenging something. The ‘coolness’ of the trend comes from the idea that we are part of the counterculture while we literally wear this identity on our sleeves” (Simon 23). So why, then, can’t we realise the sort of trap that has been set for us? Where is the line drawn between genuine interest in vintage and a performative “illusion of knowledge, freedom, and participation” through temporal sartorial practices (Brown qtd. in Simon 23)?

While there is extensive literature surrounding the various aspects of vintage from the 20th century, ‘existing theories on consumption, fashion and subculture’ cannot begin to fully explain the phenomenal popularity of vintage, vintage simulation, and retro-style garments in today’s fashion industry (Veenstra and Kuipers 355). In agreement with the previously defined ersatz nostalgia, Veenstra and Kuipers add that “the nostalgia invoked through vintage entails a reappropriation and reinvention of consumer goods, rather than a longing for an actual past”. Time in the 21st century is always fleeting – trends change at an extremely rapid pace; therefore, goods are also constantly being swapped out in favour of the next popular item, encouraging constant consumption. “Individuals compensate…[the] fast-changing society…by invoking the past” as a way of halting time (Veenstra and Kuipers 356). Consequently, nostalgia is here equated with alienation – as the original meaning of the word describes a sort of homelessness, creating this romantic idea of not fitting in with one’s surroundings, from which the term “born in the wrong generation,” finds its grounds, and shows the extent to which younger generations wish to connect with the past.

Since we mainly learn about the past through social media or search engines, the details of temporal representations are often cherry-picked, providing a picture perfect image often capitalised upon by fashion brands. For example: the loving, spiritual vibe we associate with the 1960s and 1970s typically excludes the very real social issues that were happening at the same time. From the 1990s, vintage stylings flatter the contributions of hip hop and Black Culture while the gross injustices that communities of colour continually face are largely ignored. We see the 20th century as a golden age, fetishizing pasts that are “all too easily manifested into product,” and in many cases we are satisfied with that (Simon 24). The reason that we, as a society, accept the pretty packages in which nostalgia is sold to us is due to the “psycho-economic game of neoliberalism,” where big brands and vintage feelings not only coexist but thrive off each other (Simon 24). This can be seen in big-brand case studies such as Brandy Melville and Urban Outfitters, whose “vintage simulation” is manifested in collections of reproduced vintage styles, such as high-waisted, slightly tapered jeans reminiscent of the 1980s or selections of distressed flannel shirts, each one different in order to deliver an “authentic thrifting experience” (Simon 21).

Notice Brandy's choice of words: "Kenzie 90's Denim Skirt" instead of "90's-style" or "90's-inspired"

Branded nostalgia encourages us to view the past through rose-tinted glasses, ignoring the social and economic struggles that ribbon through history, essentially sterilising entire eras down to clothes, music, and “vibes”. Leone describes the use of nostalgia as the last great ‘Trojan horse [of marketing] into the agency of the consumer’, but by this point nostalgia is a tool that businesses must hang onto for dear life (Leone 2).

As long as consumers, in this game of make believe, remain unphased by the commodification of nostalgia, the mechanisms of neoliberalism will continue to obsess and distract consumers while the industry of selling temporality continues to thrive.

Fashion, Style, and Taste

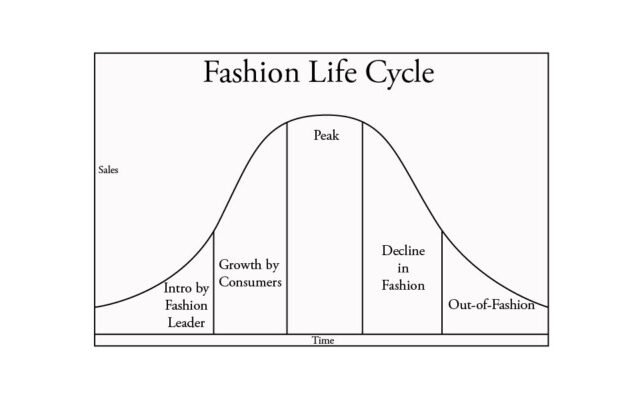

The explosive popularity of vintage and retro style garments in the 21st century must be attributed in part to the fashion industry and the cyclical nature of fashion itself. Georg Simmel’s seminal 1957 essay titled ‘Fashion’ provides an antiquated yet surprisingly relevant basis for understanding the industry while shedding a critical light on the many facets of fashion and all things considered fashionable.

Garments from the 1950s are not directly included in the latest wave of retromania (although some details may be incorporated into various stylings). They are represented in a more niche group of vintage performers that might have more know-how on the fabrics, maintenance, and pairing of garments such as pedal pusher trousers or a petticoat and shirtdress. However, this is not to say that 50s and 60s fashion didn’t have its own moment in the spotlight – just look at the hipsters and “twee” girls that dominated the early 2010s Tumblrscape.

The height of the 50s wave of retromania came shortly after the series Mad Men aired in 2007. The near-impeccable costume and set designs really compelled audiences to imitate the clean and chic mid-century modern look in their own spaces (Jenß 108). While garments of this period would still be considered treasures if found by the right people in the right condition and size, the eras of interest today - referenced in somewhat niche aesthetic categories such as nostalgiacore, thriftcore, and retrofuturism - include the 1960s, 1970s, and the 1990s (Aesthetics Wiki). Simmel’s work provides a firsthand perspective into what fashion was like then, and how it doesn’t seem to have changed much in nature since. It’s worth noting that the silhouettes and garments produced in the time of the essay have already made their way through the cycle, having been left in the hipster era and abandoned for the styles of the next decades.

Costume design by Janie Bryant made the world of Mad Men that much easier to escape to

Elizabeth Moss as Peggy Olson in season 7 of Mad Men

According to Simmel, fashion has many functions. It is defined as being “the imitation of a given example…satisfy[ing] demand for social adaptation” and furnishing a general condition, effectively boiling down the behaviour of the individual into a group tendency – consumer behaviour (Simmel 543). Fashion separates time and social stratum, uniting one class while alienating others in their quest to keep up. It imitates the given example while simultaneously creating a status quo (Simmel 544). This dualism, both for the individual and the collective, highlights a paradoxical need to both fit in and stand out. In fashion there is an expectation – set by the elite – to accept the pace and flow of trends complacently, always playing carefully by the rules. This dynamic between the ruling class and imitating classes in fashion plays a crucial role in cementing the principles of society into cooperative public action, even outside the sphere of fashion.

Simmel characterises fashion’s campaign by simple cycle, but first notes that oftentimes “not the slightest reason can be found for the creation of fashion from the standpoint of an objective, aesthetic, or other” aspect (Simmel 544). From this it is assumed that the expression and narratives found in contemporary analyses of dress are irrelevant to the idea of fashion itself, and creativity largely comes when being fashionable is not the focus. However, the novelty granted by “foreign origin” is considered to be a swaying factor in the choosing of fashions by the elite. Simmel writes: “Whatever is exceptional, bizarre, or conspicuous, or whatever departs from the customary norm, exercises a peculiar charm on the man of culture,” which contributes to the constant desire for novelty among the wealthy. Deviance from the status quo is only acceptable sometimes, usually at the discretion of a “taste-maker” or “influencer” in today’s vocabulary.

This dress from ‘My Date with the President’s Daughter’ fits right into today’s Y2K trends

According to Simmel, the birth of a fashion depends on the whims of the upper class. It is the elite, essentially, who choose what will be “in fashion” at any given time. The styles then trickle down to the middle and lower classes who scramble to produce, imitate, and adopt these designs at a quicker rate, which produces more of these garments, therefore driving down the price to accommodate lower socioeconomic spheres. In parallel, the fashions appointed by the upper class must still be adopted by the masses for it to be considered “in fashion.” Its exclusivity is precisely what allows fashion to dominate so much space in social systems. It “represents a standard that can never be accepted by all,” leaving some scrambling to catch up or to maintain their pace in the race, a feat that is easier said than done in a society where change is seemingly the only constant (Simmel 549).

Kim's look by Yeezy hasn't aged a day compared to today's top search results for "neon pink club dress"

A unique characteristic of fashion is that, as Simmel writes, it is not found in “primitive” societies where “primitive conditions of life favour a correspondingly infrequent change of fashions” (546). This is due to the lack of strong sense of hierarchy that more “advanced” societies possess (remember, this was written in the 50s). Simmel poses an interesting point here that makes the so-called “advanced” society actually seem far less so. In a “non-primitive” society, there are institutions like fashion that have no sense or reason, where the different classes allow themselves to be herded into one category or another, eating all that they are fed without question. So-called “primitive” societies care far less about how they appear, and do not have the same social competition and envy that members of the “advanced” society are faced with.

While it may be outdated in some respects, this text can still be used to analyse the state of the fashion industry today. Simmel couldn’t imagine the accuracy of his predictions, which guessed that the speed of the trend machine and the demand for new fashions would only increase with the increase in wealth. His observations foreshadowed the socioeconomic impact of a constant need for change while still enforcing uniformity through the mass production of designs.

Watch how trends enter "in fashion" and promptly leave. This cycle today moves at an alarming rate.

According to Simmel, “changes in fashion reflect the dullness of nervous impulses [of a given generation]: the more nervous the age, the more rapidly its fashions change, simply because the desire for differentiation…goes hand in hand with the weakening of nervous energy” (Simmel 547). We’re insatiable - our endless options give us the idea that we’re in control - but that illusion of choice only contributes to our general condition. Fashion itself can be defined in terms of its fleetingness: when “we feel certain that the fact will vanish as rapidly as it came, then we call it a fashion” (548).

‘Fashion’ and Fast Fashion

As mentioned in Part 1 of the series, the state of the contemporary fashion industry (first-hand consumption only) can roughly be split up into a few categories. The first, “fast fashion,” is characterised by a rate of production so fast it seems humanly impossible (and certainly unsustainable). With new designs being made available on a monthly or even bi-weekly basis, fast fashion brands are dominating the market. Then there are luxury and couture brands, which largely target upper-class consumers while still making their elite-ness known to the masses, namely through social media presence and in print media. Then there are the smaller, sustainable producers that tend to fall between dirt-cheap and break-the-bank-expensive – but are still inaccessible to many.

Zara, H&M, Forever21, and Urban Outfitters are some of the biggest brands in fast fashion, both digitally and in-store. However, in recent years, these huge names have made way for now-giants like Shein, whose business model is essentially a trend machine – churning out styles so fast that the previous month’s looks hardly got a chance to gain traction. The fashion industry today, more than ever, promotes constant consumption, replacing last week’s wardrobe with a new one and discarding things that aren’t in fashion anymore. This only speaks to the fickleness of fashion – something that generally holds great importance in society – whether one is styling designer or on a dime. Yet there seem to be two ways to be fashionable –one being to adopt whatever is trendy at the time; the other, more elusive, identified in the famous saying that “fashions fade, style is eternal” (Harper’s Bazaar UK).

But what about taste? Fashion, style, and taste are terms we often hear used together, in similar contexts and sometimes even synonymously (i.e. being fashionable and stylish are often used interchangeably). From the works of Simmel, Hebdige, a British sociologist, and Bourdieu, a French sociologist, we can conclude that taste is little more than a class construct, part of the trickle-down effect of the preferences of upper classes on the masses, but other readings of taste provide some room for interpretation.

In Travelling Light: One Route Into Material Culture, Hebdige cites Bourdieu in explaining the struggle of justifying a concept so subjective as taste “Tastes (i.e. manifested preferences) are the practical affirmation of an inevitable difference…(i.e. the difference between a cultivated bourgeoisie and an ‘ill’-or-under-educated mass)…asserted negatively by the refusal of other tastes,” forcing life into categories of good and bad, encompassing all aesthetic categories into a mould set by the elite (qtd. in Hebdige 11). In other words, there can’t be “good taste” without “poor taste” to compare it to, to look down upon. Within this framework, taste, and “opposing taste formations,” are constructed from the meanings given to different commodities and other objects. Semiotic readings play a large role in the vintage phenomenon, as objects marketed as nostalgic are considered fashionable; in good taste right now, not because of what they are but what they represent (Leone). The feelings of uniqueness, sustainable and responsible consumption, and the desire to connect with a simpler past are the emerging attitudes and practices that seem to be responsible for the popularity of vintage and thrifting.

Contrary to the suggestions of Simmel, Kantian theory suggests that the nature of aesthetic preference is so subjective that demanding universal standards for beauty, “as if beauty were a property,” is arguably a sign of primitivity in itself (Kant xlvii). According to Kant, taste – or judgement of taste – is somewhat of an equalising force. This theory does not, however, defend the validity of taste at all. “The judgement of taste exacts agreement from everyone,” he states, “and a person who describes something as beautiful insists that everyone ought to give the object in question approval and follow suit in describing it as beautiful” (Kant 34). Again, these theorists are further confirming how objectively meaningless these concepts are, and that any importance they hold is nothing more than what we’ve given to them.

Our systems of judging aesthetics, what is considered beautiful, in good taste, or fashionable, are so unique to our species that it is hard to find solid ground to justify such systems. Objectively, it seems like a concept that aliens looking in on humanity would scratch their heads at.

Since Old Man Kant’s perspective on taste doesn’t cover any contemporary criteria for judging aesthetics, we can define taste – in line with Hebdige and adding to Bourdieu’s theories on cultural capital – as a product of class, making the relationship between fashion, taste, and style a bit clearer. Not to say that our beauty standards have changed much since the 18th century, but our two-category system of pretty and ugly is showing signs of evolution, with greater inclusivity and representation seen in the fashion industry, among others.

From Simmel’s analysis of fashion and the understanding that taste is closely linked with the forces of fashion, it may be assumed that style can be thrown in the mix interchangeably. However, I believe style to be something of an essence, as described by the many iterations of the words of Coco Chanel, St. Laurent, and Lilly Pulitzer. “It isn’t just about what you wear, it’s about how you live,” (there is a lengthy article dedicated to 50 Timeless Quotes About Why Style Is More Important Than Fashion); “Styles, like everything else, change. Style doesn’t; Style is when they’re running you out of town and you make it look like you’re leading the parade.” (Jensen III 2015). While they may seem cliché or ironic, especially coming from within the world of high fashion, there is a common thread throughout these sentiments. There seems to be a key element that sets a stylish person apart from the rest and is a tool for establishing oneself a symbol in pop culture.

Style is indeed elusive, and it is not for sale. Those who have it, know it, as do other people. It’s something we can’t quite put a finger on, but we know it when we see it. It seems to be a powerful force, as fashion holds great importance in several spheres and industries. While style cannot be bought, per se, being stylish is an acknowledgment of both having taste (namely high or good taste) and being in fashion. For both Simmel and Hebdige, to be stylish - no matter by means of second-hand or designer fashions – is to be deserving of a space among the elite. Here style can be weaponized - to say a member of the elite has no style is to say they don’t deserve their position, whereas a member of the lower classes who has style can pass for an elite, which could elicit a mixed reaction should they be “found out” as an outsider. In the vintage community, style - recognized by members of both upper and lower classes - is achieved with a combination of know-how and intuition to see beauty in what others could truly consider to be trash and reflect that in a way that others can acknowledge.

The referenced work of Hebdige analyses the creation and maintenance of subcultures, focusing on the Punk and Mod subcultures of the 1960s. While the findings of these groups don’t directly relate to groups surrounding Vintage, we can use elements of the subcultural framework, in particular the practice of bricolage, as a working definition for style. Hebdige follows French anthropologist Lévi-Strauss (no relation to the jeans) in breaking down the practice and the player – the bricoleur – who constructs “implicitly coherent, though explicitly bewildering, systems of connection between things that perfectly equip their users to ‘think’ their own world,” and systematically manifest them into physical symbols. While Levi-Strauss stresses that this is the way in which “the non-literate, non-technical mind” makes sense of the world, he also acknowledges that, “far from lacking logic,” bricolage is a “science of the concrete” (as opposed to our ‘civilised’ science of the ‘abstract’) (Hebdige 135).

CTRL+C, CTRL+V: Mondrian (left) "inspires" Yves St. Laurent 1965 fall/winter 1965 collection (center) and finally the more affordable Spiegel 1966 catalog (right).

Next to bricolage is pastiche, whose approach is much more like a “copy + paste” from other works. “Bricolage is able to create new meaning from the old while pastiche is just referencing the old for what it means,” which is often easily spotted in pop cultural works such as collections or campaigns (Oney 2010). Pastiche is often used in high fashion, with designers like Jeremy Scott (of the Moschino fame) and even Yves Saint Laurent taking more than inspiration from pop culture for the runway (Oney 2010). Bricolage, in this case, can be likened to the vintage performer, who takes the elements from the past as they exist - as opposed to mass-reproduction as the means to a corporate end (thanks, Kant). Instead, the result is a look that evokes a somehow deeper feeling, more attainable and familiar, than something on the runway or in a gallery. Whatever you call it, the art of creating meaning from fragments of reality is manifested in countless ways in popular culture. In music - especially in Hip Hop - there is sampling; in art, countless movements such as Arte Povera or DIY culture; in film, one finds classic shots and frames recycled by the likes of Tarantino and other pastiche filmmakers. In short, it is hard to find something – anything – that we haven’t seen before in some way, shape, or form.

However, the success of these creations is entirely dependent on the way in which we view, judge, and receive them. Our system of evaluation essentially boils down to three factors: the maker, whose background, intentions, skills, and ideas must provoke thought, challenge existing conditions and systems; the elements adopted from other works that must be combined in such a way that the original context is either confronted, repurposed, or distorted enough that its meaning and connotation are changed totally; and the resulting product itself - to what end is it destined? The current generation of digital natives is a discerning group, capable of seeing right through corporate attempts at relevance - which makes them a tricky market to reach. They can tell which messaging and imagery feels forced, manufactured, or out-of-touch, but the criteria for these judgments is highly elusive and hard to define. How do we evaluate authenticity? What even is authenticity when true originality is hard to find?

In Part 3, we will be talking about all things Subcultures, Authenticity and Aura…

Bibliography:

Bruggeman, Danielle. “Fashioning Memory: Vintage Style and Youth Culture.” Fashion Theory: The Journal of Dress, Body & Culture 21, no. 3 (May 2017): 317–22.

Hebdige, Dick. “Travelling Light: One Route Into Material Culture.” RAIN, no. 59 (December 1983): 11-13. https://doi.org/10.2307/3033466.

Hoffower, Hillary, and Andy Kiersz. “The 40-Year-Old Millennial and the 24-Year-Old Gen Zer Are in Charge of America Right Now.” Business Insider, Business Insider, 26 Sept. 2021, https://www.businessinsider.com/24-gen-z-trends-40-millennial-spending-changing-economy-2021-9.

Jenß, Heike. “Cross-Temporal Explorations: Notes on Fashion and Nostalgia.” Critical Studies in Fashion & Beauty 4, no. 1/2 (October 2013): 107–24.

Jensen III, Lorenzo. “50 Timeless Quotes About Why Style Is More Important Than Fashion.” Thought Catalog, The Thought and Expression Company LLC, 22 May 2015, thoughtcatalog.com/lorenzo-jensen-iii/2015/05/50-timeless-quote s-about-why-style-is-more-important-than-fashion/.

Kant, Immanuel. "Critique of judgment.” Werner S. Pluhar (trans.). Indianapolis: Hackett (1987).

Oney, Ece. The Postmodern: Bricolage & Intertextuality, Parsons Paris School of Art, 15 Jan. 2010,fashionmedium.blogspot.com/2010/02/bricolage-intertextuali ty.html#:~:text=Pastiche%20is%20a%20playful%20reference%20to%20 a%20master%20work.&text=Bricolage%20is%20able%20to%20create,med ia%20and%20is%20called%20intertextuality.

Simmel, Georg. “Fashion.” The American Journal of Sociology 62, no. 6 (May 1957): 541-558. http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0002-9602%28195705%2962%3A6%3C 541%3AF%3E2.0.CO%3B2-2.

Torossian, Ronn. “Can Your Marketing Connect with Gen Z in 8 Seconds?” Agility PR Solutions, Innodata, 10 Apr. 2020, www.agilitypr.com/pr-news/public-relations/can-your-marketing-connect-with-gen-z-in-8-seconds/#:~:text=But%20its%20most%20inte resting%20revelation,compared%20to%2012%20for%20millennials.

The Investopedia Team. “Trickle-down Effect.” Investopedia, Dotdash Meredith, 8 Sept. 2021, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/t/trickle-down-effect.asp#:~:text=In%20the%20world%20of%20fashion%2C%20trickle%2Ddown%20describes%20a%20situation,those%20in%20the%20lower%20classes.

Images:

Esquire. 2018. Available at: https://www.esquire.com/style/mens-fashion/a22023566/back-to-the-future-nike-sneaker-auction/ [13 June 2022]

Sneaker News. 2016. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NimGxU4Qnhk [13 June 2022]

De Zeen. 2021. Available at: https://www.dezeen.com/2021/01/12/burger-king-rebrand-retro-logo/ [13 June 2022]

Tumblr. 2018. Available at: https://thats-so-2000s.tumblr.com/post/173379108588/name-the-bedroom [13 June 2022]

iNews. 2020. Available at: https://inews.co.uk/culture/television/mad-men-10-peggy-olson-real-hero-79472 [13 June 2022]

Front Row Features. 2015. Available at: https://frontrowfeatures.com/photo-gallery/photos-jon-hamm-co-reflect-on-mad-men-11491.html [13 June 2022]

Popsugar. 2018. Available at: https://www.popsugar.com/fashion/Kim-Kardashian-Pink-Dress-Kylie-Jenner-Birthday-2018-45153939 [13 June 2022]

Mood Sewciety. 2020. Available at: https://www.moodfabrics.com/blog/why-is-fashion-important/ [13 June 2022]

Wheretoget. Available at: https://wheretoget.com/magazine/when-art-inspired-fashion-2017 [13 June 2022]

Sienamystic. 2012. Available at: https://vintage-ads.livejournal.com/3127079.html [13 June 2022]