Women Artist Series - Alina Szapocznikow.

Chapter 1 - Imprints.

I came across Polish Born artist Szapocznikow (pronounced shuh-potch-ni-koff) a couple of months ago, when reading into trauma theory for my dissertation. Featured in Chapter 4 of Griselda Pollock’s ‘After Affects | After Images - Trauma and aesthetic transformation in the virtual feminist museum’, the chapter talks about Szapocznikow’s sculptures as a site for ‘encrypted trauma’ [Pollock, 2013][1].

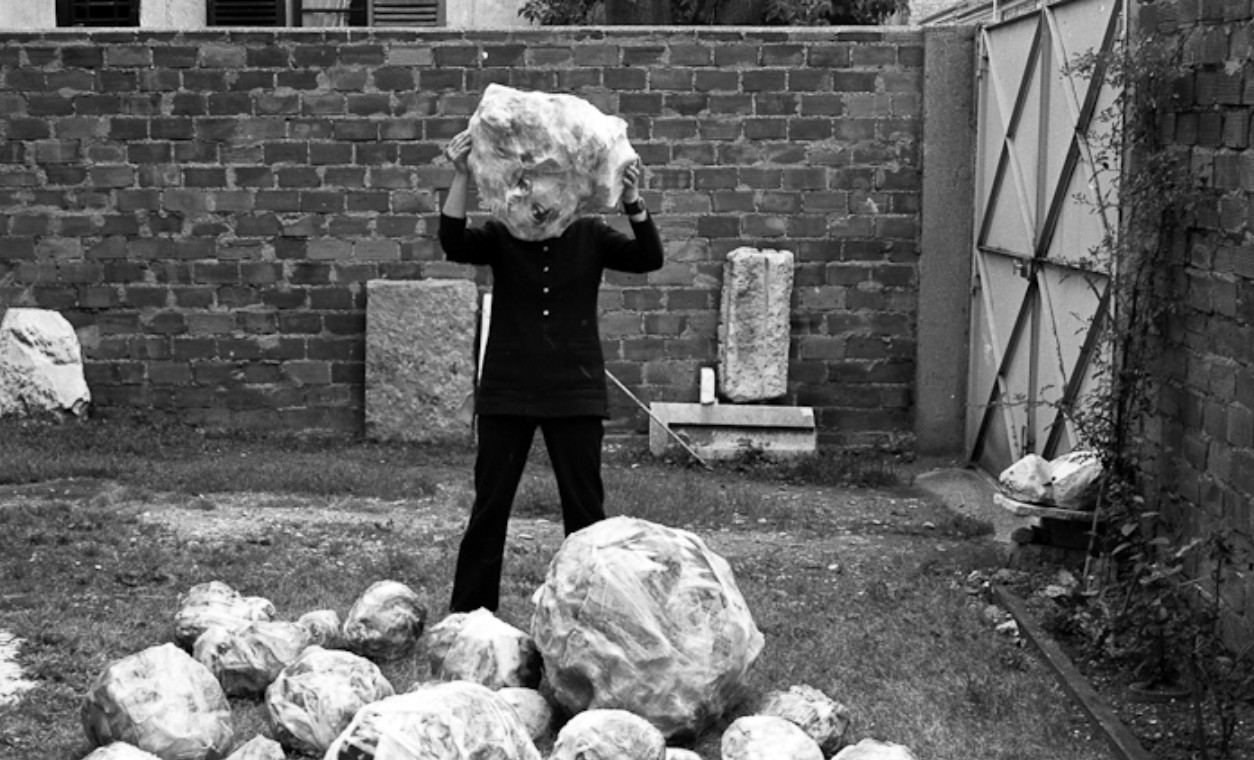

Alina in Malakoff Studio, France (1971)

Alina’s early life was indeed traumatic. Her father died from Tuberculosis just before World War II, and her jewish identity meant that her life was constantly jeopardised. At just 13 years old, Szapocznikow worked with her mother at a hospital for two years, situated in a ghetto in Pabianice. Also travelling to Bergen-Belsen concentration camp via Auschwitz, Alina was exposed to the horrors and atrocities of the holocaust until 1945.

Escaping the traumas of post-war Poland, Szapocznikow moved to Prague to study sculpture. Studying at Otokar Velimsky’s studio and The Academy of Art and Industry, Alina then continued her education at École national supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where she would meet her first husband - Polish art historian Ryszard Stanislawski. Szapocznikow spent her early career as an artist between both Prague and Paris. In 1951, Alina fell ill to Tuberculosis. Her survival was dependant on an experimental antibiotic drug [Higgins, 2017][2]. After her recovery, she adopted a son with her then-husband, before continuing to make art.

Although distinct in style, Alina’s early work was mostly formal and figurative. It wasn't until the end of Stalin’s life in 1953 that Szapocznikow began to create abject disembodiments, such as her bulbous ‘Lampe-Bouche’ (1966). Inherently sensual and playful, Alina illuminates and multiplies her own lips in an arrangement which defies regular corporeal composition [Sienkiewicz, 2009] [3]. By subverting traditional methods of sculpture, Alina attempts to reclaim and understand her own body through the process of sculptural fragmentation; Although you could also argue that her work can be read through the lens of female objectification.

This motif of her own lips is a prevalent theme in her work. The repetition of her mouth - an agent of voice - may be a manifestation of Szapocznikow’s lack of verbal communication about the traumas she experienced in concentration camps. This compulsion to sculpturally repeat a closed mouth creates a figurative Army of Silence, whilst aesthetically encapsulating the damaging effects of her own suffering.

‘Multiple Portrait (Double)’, 1967

“I only produce clumsy [or awkward] objects. (Objects maladroits)...”

Another notable work of Szapocznikow’s is her ‘Photosculptures’ - a series of superimposed photographs of various chewing gum formations made by the artist. I find it interesting that she uses the unconventional and abject material of chewing gum, to then decide to display the sculptures through photographs, making them more ‘digestible’ [Pollock, 2013][1]. This dematerialisation of the sculpture loses an element of the gum’s repulsive quality. The process of chewing and spitting contrasts that to her previous casting of her own body parts. Szapocznikow now uses her mouth as a tool to manipulate the material itself, forming a new type of ‘Objects Maladroits’.

“Despite everything, I persist in attempting to fix in resin the imprints of our body: I am convinced that among all manifestations of perishability, the human body is the most sensitive, the only source of all joy, all pain, all truth.”

Illness was prevalent throughout Alina’s life, and her preoccupation of death manifested through her works, particularly in her final years. Although Szapocznikow fell very ill to peritoneal tuberculosis in 1951, it was her 4 year battle with breast cancer which ultimately cut her life short in 1973. Alina came to terms with her own mortality by transforming what was inside, out - hence her work ‘Envahissement of Tumers’ (1970). The disproportionate materialisation of tumours perhaps translates the overwhelming anxieties Szapocznikow was feeling as her life was drawing to a close. Reading Szapocznikow’s work from the context of a holocaust survivor and infertile woman, as well as cancer patient - I’m perhaps suggesting that the invasive leakage of swelling forms might not only depict her trauma with cancer, but her trauma with life.

Art allowed the space for Alina to release a narrative so damaging, which she could not convey through words. As a viewer, we have to read the absurdity of her sculpture through the lens of her own personal traumas. Szapocznikow’s work conveys a certain fragility and anguish, casted from the imprints of her own body and experience. It is this materialisation of trauma, casted by the tortured artist which makes her work so raw and honest.

Bibliography:

[1] Pollock, G. (2013) After Affects | After Images - Trauma and aesthetic transformation in the virtual feminist museum. Manchester University Press, Manchester.

Available at: https://irwag.columbia.edu/files/irwag2/content/pages_from_ch_4pollock_after-affects_revised.pdf

[2] Higgins, C. (2017) ‘Body shock: the intense art and anguish of sculptor Alina Szapocznikow’ The Guardian.

[3] Sienkiewicz, k. (2009) ‘Multiple Portrait - Alina Szapocznikow’ Culture.pl.

Available at: https://culture.pl/en/work/multiple-portrait-alina-szapocznikow

Illustrations:

From the Archive of The National Museum, Cracow. Owned by Stanisławski P.

Available at: https://artmuseum.pl/en/archiwum/archiwum-aliny-szapocznikow