Where Should We Present Queer Art?

Figure 1, Harmony Hammond “Inappropriate Longings”, 1992. oil, latex rubber, and linoleum on canvas with metal gutter, water trough, and dried leaves. 7 1/2 x 18 1/4’.

Introduction

In Cray-Stanton’s essay, Queer Contemporary Art: The Responsibility of Visibility, they discuss how fine art can be a unique and powerful form of queer representation. In contrast, media depictions of queer people have often perpetuated harmful stereotypes and under-represented the broadness of queer experience (for example, having a singular queer character with a specific narrative). Whereas, the culture around art encourages personal interpretation of the work, allowing visibility for a range of queer experiences. Cray-Staton references Harmony Hammond’s piece Inappropriate Longings as an example of this. Inappropriate Longings (figure 1) is an abstract art piece, creating with oil paint, latex, and linoleum, accompanied by a metal trough surrounded by sticks and dried leaves. The phrase “goddamn dyke” is carved into the left panel, making the painting explicitly queer. Hammond has made a decision to convey the experience of violence against queer people through materiality and metaphor, rather than figurative or bodily depictions. This nuanced emotion is what Cray-Stanton suggests make fine art a great medium for queer visibility, as its lack of reliance on bodily depictions allows for the work to resonate with a wider range of queer people and experiences.

This emphasises the need for queer visibility in art, as it presents a more intersectional form of representation. In recent years, legislative changes recognising same-sex relationships have been turning points in the acceptance of queer people (Aksoy, Cevat G. et al.). As a result, queer artists have been given more opportunities to present their work in major museums and galleries. However, many of these galleries have histories of excluding and censoring queer art in their collections - a complex problem which still remains unaddressed. How should the relationship between queer artists and major art museums be navigated now that places that once oppressed queer culture want to celebrate it? Is it worthwhile for queer artists to assimilate into these institutions in pursuit of greater visibility?

Part 1. The Past (2002 - 2011)

The prior treatment of queer art and art and artists is important knowledge for contextualising the discussion around where queer art is, or is not, presented. In their work, We Were There, We Are Here: Queer Collections and Their Repositories and Legacies (2017), Alexandria Deters chronicles many examples of what she defines as queer erasure: the removal of queer elements or queer art entirely from collections using a range of means. She discusses her own experience with the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation and their erasure of the queer elements of his life (pp. 12-17). The foundation fails to mention any of Rauschenberg’s non-heterosexual relationships - for example his relationship with Jasper Johns, one which greatly influenced his work. However, Rauschenberg’s ex-wife and biological son are mentioned throughout. Deters suggests that because of this erasure, Rauschenberg’s sexuality can be assumed as heterosexual. The Director of Archive and Scholarships for the Rauschenberg Foundation suggested that Rauschenberg wanted to be seen as an artist, rather than a gay artist. In response, Deters writes:

“While it is important to respect Rauschenberg’s intentions when it comes to how he wants his art seen, it is important that his sexuality is seen and discussed as well. Not because it directly reflects his art practices, but because by acknowledging his sexuality it shows queer children today and in the future that their sexuality does not have to define them and does not have to be a hindrance to having a successful life.”

Here, Deters expresses the reason why it is important to recognise an artist’s queerness, even if queerness was not a central topic explored in their work. While Rauschenberg might not want to be known for his sexuality alone, this is not a justification for his Foundation to remove these important elements from his history. The issue of artists becoming defined by their sexuality is something institutions like the Rauschenberg Foundation should be deconstructing, rather than circumnavigating. This example shows how queer elements of artists’ lives are omitted by art institutions, resulting in a lack of visibility for queer people and a continuation of the ideology that non-straight sexualities should be kept private.

Figure 2, Andy Warhol “Male Nude”, 1957. gold leaf and ink on coloured graphic art paper. 17 x 14 inch

Deters also references the Andy Warhol Retrospective, held by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles (May 25, 2002 - August 18, 2002), as an example of an art show that features queer erasure (pp. 8-11). The retrospective showed over 200 paintings, drawings, and sculptures, but lacked any of Warhol’s work that explicitly referenced sex. Holland Cotter’s review of the Retrospective in The New York Times highlights the reasoning as to why this censoring of Warhol’s work is problematic:

“Try to imagine a Picasso retrospective without sex. No penises, no breasts, no vaginas. No artist having his way with his studio models, no men and women joyously in flagrante. It’s out of the question; sex was too much a part of his work. It was a main ingredient in Warhol’s, too. He did a whole series of sexually explicit paintings and took hundreds, probably thousands of explicit photographs. You don’t see any of them here. ”

The removal of sex from the retrospective means that the depiction of Warhol is innately flawed, because unlike Rauschenberg, sex and sexuality are key themes explored in his body of work. Whilst Warhol’s retrospective was not completely sexless, the major neutering of his explicitly queer work curated by the gallery creates an incomplete image of Warhol’s life and work. Cotter’s review suggests that it is this queer, same-sex nature of Warhol’s explicit work that led to its omission in the retrospective.

Figure 3, Willem de Kooning “Two Women with Still Life” 1952. Pastel, charcoal on paper.

A response to Cotter’s review suggests that the reasoning behind the lack of explicit content in the retrospective is for it to be child-friendly (Stankard, 2002). However, just one month prior to the Andy Warhol Exhibit, the MOCA presented an exhibition on Willem de Kooning’s drawings of the female form. Here is a description of de Kooning’s work from the exhibition catalogue:

“In 1951, de Kooning abruptly returned to depicting women. Using turbulent brushwork, he turned the female figures into monumental, intentionally vulgar, wildly distorted images whose parts read alternately as flat patterns and fully rounded forms. The effect is an almost violent sensuality. ”

The description of the work shows that the Museum of Contemporary Art were not only willing to show artwork that touched on explicit, vulgar themes, but they were willing to intentionally recognise this in print when it came to de Kooning’s work. This suggests that Warhol’s explicit works could not have been omitted for having sexual content, as arguably, many of de Kooning’s works could be said to be of a similar nature. It is rather the fact that de Kooning’s work implied heterosexuality, whilst Warhol’s implied queerness. De Kooning’s use of vulgar imagery is allowed to have a nuanced exploration, whereas Warhol’s is simply branded as inappropriate. Excluding works that depict queerness not only prevents a full depiction of Warhol’s life in his own retrospective, but it also restricts discussion around these works and how they explore Warhol’s sexuality.

The argument that the retrospective should be presentable to children is flawed because straight artists are not held to this requirement. ‘Think of the children’ is an argument held so commonly against queer people that it has become cliché. Being used to protest against same-sex marriage*(1), LGBTQ education in schools*(2), transgender people having access to healthcare*(3), and drag queen performances*(4), I find it to be apparent that this argument is only an attempt to prevent queer activism, as it comes from a perspective of believing that queerness is inherently inappropriate and other.

These two examples show how galleries have previously been unwilling to recognise the queer elements of an artist’s life, whether it is additional information like Rauschenberg, or integral to the work like Warhol. Specifically, they show a reluctance to mention the queerness of artists who are already well-established figures in visual culture, as if this detail of their lives or work in some way soils their reputation. The lack of queer art seen in galleries was not caused by a lack of queer artists, instead it is the fault of institutions that have repeatedly excluded queerness from their spaces. In contemporary discussion of creating inclusive spaces, this history of malicious exclusion is often swept under the rug, as if queer people and other minorities were missing from these spaces by coincidence, rather than by design.

*(1) Mark Regnerus’s paper “How different are the adult children of parents who have same-sex relationships?” was referenced as “evidence” that same-sex parents damaged children. Derba Umberson, a fellow sociologist at the University of Texas discusses the flaws of this study in her article.

*(2) “At one protest they held signs that read “say no to promoting of homosexuality and LGBT ways of life to our children”, “stop exploiting children’s innocence”, and “education not indoctrination”.” – Birmingham school stops LGBT lessons after parents protest, The Guardian.

*(3) I’m concerned about the huge explosion in young women wishing to transition and also about the increasing numbers who seem to be detransitioning.” – J.K. Rowling Writes about Her Reasons for Speaking out on Sex and Gender Issues, J.K. Rowling. It should be noted that transgender people only make up 0.5% of the population in the UK (Census), and Pablo Exposito-Campos’s article explains the nuances around gender detransition.

*(4) Jones, Tim. “‘I’m just trying to make the world a little brighter’: how the culture wars hijacked Drag Queen Story Hour” The Guardian, August 2022.

Part 2: The Present

In the present day, there seems to be an increasing number of opportunities for queer artists, and many major museums and galleries have presented queer art since it entered the mainstream. However, given the prior treatment of queer art and artists, these opportunities should be scrutinised as the intentions of these institutions are unclear.

A more recent example of a contemporary queer art exhibit was the Tate Britian’s Queer British Art, in 2017. The exhibition described itself as the first show dedicated to the subject of queer british art, presenting a range of queer artwork from 1861 to 1967. The time-period that the exhibition focuses on means that many of the artworks present coded and subtle displays of same-sex attraction and gender nonconformity. The intention behind the exhibition was to recover stories and lives told in art that had previously been removed, since much material of this topic had been either lost or destroyed (Tate Britain). The exhibition was criticised for a range of reasons. Some critics suggest that grouping art based on the artist's sexuality is wrong, as this information should not be relevant when consuming their art (Street Porter, Battersby). I find this criticism to be flawed as the Tate Britain state that the intention of the show is to amend queer erasure in art history, and the idea that sexuality should be irrelevent to these artists’ lives is dismissive of the history of oppression many of the artists in the show have experienced. Alternatively, the gallery was criticised for its incomplete depiction of queerness. The gallery features primarily white, male, wealthy artists which means there is a lack of representation of other queer histories (Emelife, Hudson). The show was also criticised for its lack of through-line, as many of the works and their descriptions danced around heavier topics of queer expression. Whilst some of these factors may be the result of the time period the exhibition focuses on - as queer art was unlikely to survive unless it was created by someone with other privileges - it brings into question why the Tate Britain would not adapt the scope of this exhibition to present an inclusive queer history (Cumming, The Guardian). Cumming’s review highlights this, where she writes:

“But it’s easy to imagine a show of all these artists and more, in which the works would enrich each other while carrying the narrative of gay British history down the decades. But this confused, uninspiring and peculiarly sedate survey is not it. ”

Whilst the show is successful because many of the artworks present are recognised as profound visibility for queer people, it lacks in other crucial areas. Biases against women and people of colour are not addressed, suggesting that there has been no real change to the treatment of other minorities within the institution as a result of this show. The seemingly lacklustre and inconsistent value of the show suggests that it was in some ways performative, and I feel that the institution's overall depiction of queer art is unsatisfactory. It brings into question the intentions behind the exhibition's production - what other motivations do institutions have to create these minority-focused exhibitions?

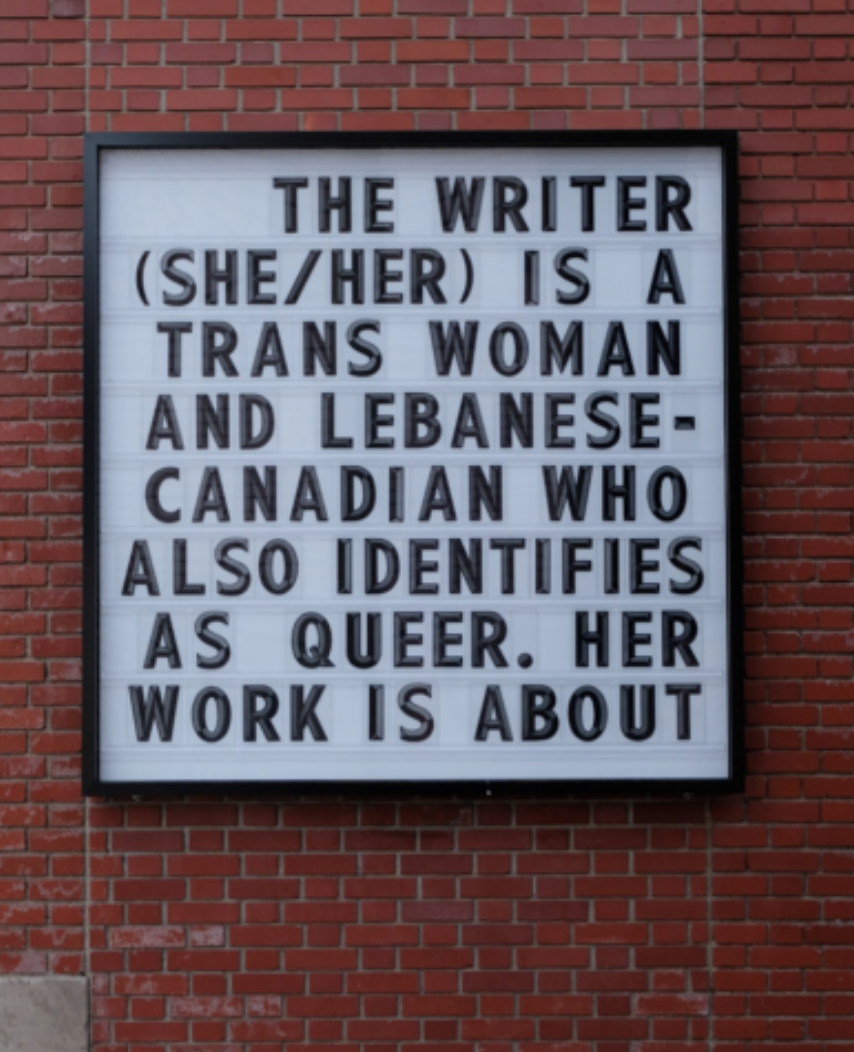

Anna Deliza created the piece Artist Bio on the contemporary treatment of queer creatives. In her statement for the piece she discusses the ulterior motives of institutions presenting queer art, writing:

“The institutions know, as well as we, that their support of marginalised artists protects them from the scrutiny to which they are typically susceptible. That scrutiny being, they are usually white, capitalist institutions funding the work of white, rich artists. The more an artist’s work can distract from the institutions’ support history, the more they are spotlighted. As a result, marginalised artists have begun, though perhaps somewhat unconsciously or as means of survival, to focus the subject of their work on their identity. ”

Figure 4, Anna Deliza’s “Artist Bio.” 2021. Text on billboard.

“For example, as a writer who is also Lebanese and Transgender, in the last two years I have not once considered the possibility of writing a story completely separate from either of those identities. I admit that I have exploited my own identities for the financial support of capitalist institutions. While identity is certainly relevant to some artists’ work, and is often central to my own writing, it does not tell the full story. In most cases, to lead with my identity is the most hollow introduction I could give myself. ”

Here, Deliza discusses how in an attempt to reshape their own image, many art galleries now create mediocre queer exhibitions to present themselves as progressive. I find this deflective nature to sour many exhibitions, the Tate describe their exhibition to be the first to focus on queer british art, but never bring into question why they and other galleries waited so long to do so. Similarly to the Rauschenberg Foundation not working to deconstruct the idea of a gay artist, I find these galleries' aversion to discussing queer erasure to reveal their intentions to aid queer artists to be disingenuous.

Deliza also touches on the commodification of identity as transactional for queer visibility. Gay Shame, a counter movement to the commercialisation of Gay Pride, protest against the harm this causes to queer activism. Tommi Avicolli Mecca writes in his discussion on a Gay Shame Event:

“Every movement undergoes changes in three decades, but pride, especially in Los Angeles, San Francisco and New York, transformed a street protest into a multi-million dollar extravaganza that has no political through line. How could it, when gay cops march next to Lesbian and Gay Insurgents and gay atheists follow Dignity, the gay Catholic group? Except for the open displays of sex and flesh, pride in a city such as San Francisco is not much different from any other parade. Thousands stand along the sidelines and cheer every corporate contingent that passes despite the fact that many of them, while good on gay rights, have policies and practices that oppress other groups (e.g., running sweatshops in Asia). For progressives, participating in the march requires a kind of political amnesia: Ignore the bad politics ahead of you and keep your banners high. ”

Here, Mecca discusses how the commercialisation of pardes taints its political messaging, and instead becomes focused on supporting giant unethical corporations. This further shows how queerness suffers by being assimilated into the mainstream, as institutions feign progressive ideologies in order to financially benefit from the growing presence queerness has in mainstream culture.

This idea can be seen being applied to museums and art spaces in Benoit Loiseau’s article The Museumification of Queerness, where he describes visiting Queer Britain and Queercircle, two art spaces for queer art. He highlights how in Queer Britain, the presence of the corporate sponsors of the museum seems out-of-place, making the exhibitions feel disingenuous. He discusses the exhibition Chosen Families, and how the show states it was commissioned by the denim brand Levi’s. The work’s intention to look at the relationships forged between queer people is undermined by the curatorial involvement of the corporation, as Loiseau puts: “whose ‘deep relationships’ are we truly looking at?” (Loiseau, ArtReview).

Most modern queer art spaces exist within the dilemma highlighted by these examples. These spaces suffer from queerness becoming a commodity that large corporations want to exploit for profit (Pedroni), however many of these spaces would not exist without corporate sponsorship. I do not want to suggest that these exhibitions are completely redundant, as they do create imperfect spaces for queer visibility to exist within. However, I think that this model of dependency on corporations will not result in a meaningful solution to queer erasure. The financial incentive behind these campaigns means that when queerness falls out of fashion and becomes unprofitable, brands will revoke their support - a recent example of this is Dylan Mulvaney’s advertisement with Bud Light, who did nothing to support her after the transphobic backlash the advertisement received (Oladpio, The Guardian). While these spaces are an improvement, they have not resolved the issue of queer erasure and more work can be done.

Part 3: The Future

Major art museums and galleries are, however, not the only space for queer art to be exhibited. In Deters’ work, they argue that galleries created by queer collectors are an important alternative to mainstream institutions. The Leslie-Lohman Museum and the GLBT History Museum are examples of art spaces which started as personal collections that later became public galleries as the collectors saw the need for queer visibility. These spaces allow for the work to exist fully and authentically because queerness is not being tokenized within a heterosexual norm. Deters argues that these spaces are invaluable, as they provide a location for queer art and queer history to be permanently presented and preserved. (Deters pp. 24 – 33, Leslie-Lohman Museum).

However, the audience of these institutions is considerably smaller than major art museums. They are unlikely to gain mainstream attention, and are only located within progressive cities, meaning queer people who live in rural or conservative areas are less likely to experience the visibility offered by these institutions. This is not intended to be a critique at these institutions who arguably offer the best experience for engaging with queer art and queer history, but rather recognises that more resources are needed for these collections to be more accessible.

So, what is the solution? To investigate representation in a mainstream setting, I would like to discuss the music video Apeshit by The Carters. Whilst the core focus of this example is rooted in the representation of people of colour, I think that the philosophy behind this video could be applied to increase visibility of queer people and improve the relationship between queer histories and institutions. The music video takes place in The Louvre, the most visited museum in the world, and also a museum built upon the colonialist stealing of Napoleon’s rule (Siegel). Throughout the video, The Carters challenge what the Louvre represents, calling attention to its cultural robbery and erasure of black history.

Left: Figure 5, The Carters, Apeshit, directed by Ricky Saiz. 2018. Still of video – 2:05 | Right: Figure 6, The Carters, Apeshit, directed by Ricky Saiz. 2018. Still of video – 1:45.

In figure 5, a line of black dancers move in front of the Winged Victory of Samothrace. This statue, and many others from the Greek Parthenon, are a subject of cultural debate as the Greek Government has asked these museums to return their stolen property. This is a contentious issue, because if the Louvre and other museums start returning stolen works, many esteemed art institutions will find their galleries completely emptied (Brysac, pp. 76). Its inclusion in the video is symbolic of the result of this theft – still, limbless, faceless. Whereas, the dancers’ fluid and expressive movement depict their liveliness and freedom, contrasting the statue and showing the result of their liberation.

In figure 6, we see Beyonce and her dancers perform in front of The Consecration of the Emperor Napoleon and the Coronation of Empress Joséphine. They insert their bodies over the artwork, reinstating a black presence that has been removed from both the history this painting tells, and also the Louvre itself. The way the dancers obscure and eclipse the range of famous art throughout the video is incredibly powerful. The focus on The Carters and their dancers’ performance reinforces their significance, while the artwork heralded to be of importance by a white regime is reduced to being the mere backdrop of their splendour.

The Carter’s interaction with the Louvre is an admirable example that shows the strength of disrupting institutions to create liberation and visibility. They take the cultural significance of the Louvre and apply it to themselves, and by inserting themselves on top of their art, they reverse the erasure of black history. This navigation of the relationship between a minority and the institution is extremely successful, as they not only use the Louvre as a platform for their art, but call out its colonial past while doing so.

The focus on liberation, disruption, and taking authority are principals I think that contemporary queer art spaces lack. Modern queer art presentations seem to be more passive in tone and often avoid direct discussions around the role galleries played in oppression and erasure. By taking authority over the space, The Carters were able to meaningfully discuss the history of the Louvre alongside presenting joyful and loving representations of people of colour. I think that queer people should seek a similar liberation, and demand to have authority over their own narrative and history.

For example, contemporary art spaces could be more willing to let queer creators have direction over how their art is presented and described, similarly to the Louvre & The Carters, which would result in exhibitions that are more authentic and more tailored for queer people, rather than to bolster the gallery’s public perception. Alternatively, spaces that provide retrospectives for artists like Rauschenberg could not only include the queer elements of his life, but also the ways in which this queerness was minimised in his legacy. These changes would help create better queer visibility for a large number of people, and also show that these institutions fully acknowledge the history of queer erasure.

Conclusion

Queer art and queer artists have always existed. It is only the malicious erasure conducted by mainstream institutions that led to the lack of queer visibility in art throughout history. Queerness has been omitted from artist’s lives, whether it is integral to the work or not. This erasure shapes the relationship between queer art and galleries today, as performative activism is repeatedly utilised to try and obscure institution’s own histories of oppression. The assimilated version of queerness presented today by these galleries is normalised, de-politicised, and commodified. While this is an improvement from the complete erasure of queer art, it cannot be accepted as the end result in the fight for queer visibility.

The future of presenting queer art is unclear. Some queer created institutions like the Leslie-Lohman Museum allow for queer art to be presented and consumed authentically, but lack scale in comparison to major institutions. Others like Queer Britain have a larger budget thanks to corporate sponsorship; however, this leads to an interference in the true goal of the museum by the corporation’s self-insertion. The Carters’ music video ‘Apeshit’ is an example of minorities choosing to liberate themselves from the need to conform to the gallery. The video innately questions the worth society places on these institutions, as they are upheld by immoral legacies. The fame and money of The Carter's is likely why the video was able to be created, however, the ideology behind it can perhaps be carried onwards. Loiseau references Roderick A. Ferguson’s criticism of this ‘willing to institution’ – how minorities turn to institutions to obtain legitimacy, which results in damaging normalisation. To avoid queerness losing its rich meaning, through separating it from its culture and history, liberation and action must be prioritised.

This essay was inspired by Lucie Cray-Stanton’s ‘Queer Contemporary Art: The Responsibility of Visibility’.

Image List:

Cover – Laura Knight, “Self Portrait”, 1913. Oil paint on canvas.

Figure 1 – Harmony Hammond, Inappropriate Longings, 1992. oil, latex rubber, and linoleum on canvas with metal gutter, water trough, and dried leaves. 7 1/2 x 18 1/4’.

Figure 2 – Andy Warhol “Male Nude”, 1957. gold leaf and ink on coloured graphic art paper. 17 x 14 inch.

Figure 3 – Willem de Kooning Two Women with Still Life 1952. Pastel, charcoal on paper.

Figure 4 – Anna Daliza, Artist Bio, 15 November 2021. Text on billboard. 6ft x 6ft.

Figure 5 – The Carters, Apeshit, directed by Ricky Saiz. 2018. Still of video – 2:05

Figure 6 – The Carters, Apeshit, directed by Ricky Saiz. 2018. Still of video – 1:45

Bibliography:

1. Aksoy, Cevat G. et al. “Do laws shape attitudes? Evidence from same-sex relationship policies in Europe” European Bank of Reconstruction and Development, August 2018. https://www.ebrd.com/publications/ working-papers/do-laws-shape-attitudes

2. Alexander Gray Associates. “Harmony Hammond – Inappropriate Longings”. Alexander Gray Associates. Last updated May 2018, https://www.alexandergray.com/exhibitions/harmony-hammond3

3. Arts Council Windsor & Region. “New Voices: Anna Daliza.” Arts Council Windsor & Region. 15 November 2021. https://acwr.net/event/new voices-anna-daliza/

4. Battersby, Matilda. “Queer British Art at Tate Britain: Is it wrong to group together LGBT art?” The Independent. 10 April 2017. https://www. independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/art/features/queer-british-art tate-britain-lgbt-a7669581.html

5. Brysac, Shareen Blair. “THE PARTHENON MARBLES CUSTODY CASE: Did British Restorers Mutilate the Famous Sculptures?” Archaeology, vol. 52, no. 3, 1999, pp. 74–77. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/ stable/41779253. Accessed 7 Jan. 2023.

6. Bunyan, Marcus. “Review: Queer British Art 1861 – 1967” Art Blart. 24 September 2017. https://artblart.com/2017/09/24/review-queer-british art-1861-1967-at-tate-britain-london/

7. Butler, Corneila H. et al. “Willem de Kooning: tracing the figure” Museum on Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. February 2002. ISBN 0-691-09618-X

8. “THE CARTERS – APESHIT” Youtube, uploaded by Beyonce, Parkwood Entertainment. Directed by Rickey Saiz. 16 June 2018. https://www. youtube.com/watch?v=kbMqWXnpXcA

9. Caldwell, Ellen C. “What About the Art in “Apesh*t”?” JSTOR Daily. 19 June, 2018. https://daily.jstor.org/what-about-the-art-in-apesht/

10. Cotters, Holland. “Everything About Warhol But The Sex” New York Times, 14 July 2002. https://www.nytimes.com/2002/07/14/arts/art architecture-everything-about-warhol-but-the-sex.html?pagewanted=1

11. Cray-Stanton, Lucie. “Queer Contemporary Art: The Responsibility of Visibility.” Round Lemon. 3 March 2022. https://www.roundlemon. co.uk/zest-archive/queer-contemporary-art-the-responsibility-of visibility

12. Cumming, Laura. “Queer British Art 1861 – 1967 review: indifferent shades of gay” The Guardian. 9 April 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/ artanddesign/2017/apr/09/queer-art-tate-britain-review-laura cumming

13. da Silva, Jose. “Visitor Figures 2021: the 100 most popular art museums in the world – but is Covid still taking its toll?” The Art Newpaper. 28 March 2022. https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2022/03/28/visitor-figures 2021-top-100-most-popular-art-museums-in-the-world

14. de la Puente, Gabrielle, and Zarina Muhammad. “why museums are bad vibes.” The White Pube, 2 March 2022, https://thewhitepube. co.uk/ podcasts/bad-vibes/

15. Deters, Alexandria. “We Were There, We Are Here: Queer Collections and Their Repositories and Legacies”. 2017. MA Thesis. “We Were There, We Are Here: Queer Collections and Their Repositories a” by Alexandria Deters (sia.edu)

16. Emelife, Aindrea. “Don’t Rely on the Tate to Define ‘Queer Art’ – Get Out There and Discover it For Yourself.” Pheonix Mag, 2017. https://www. phoenixmag.co.uk/article/april-dont-rely-on-the-tate-to-define-queer art-get-out-there-are-discover-it-for-yourself/

17. Gomillion, Sarah and Traci Giuliano. “The Influence of Media Role Models On Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Identity.” Journal of Homosexuality, February 2011. ISSN: 0091-8369

18. Hudson, Mark. “Queer British Art 1861 – 1967 at Tate Britain, review: a tame take on gay art history.” The Telegraph, 3 April 2017. https://www. telegraph.co.uk/art/what-to-see/queer-british-art-1861-1967-tate britain-review-tame-take-gay/

19. Katz, Johnaton. “Lovers and Divers: Interpictorial Dialog in the Work of Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg.” Frauen Kunst Wissenschaft, No. 25. 1 June 1998. pp. 16 – 31.

20. Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art. “Lesie-Lohan Museum of Art: About Us” Leslie-Lohan Museum. 2021. https://www.leslielohman.org/about-us

21. Loiseau, Benoit. “The ‘Museumification’ of Queerness” ArtReview. 31 August 2022. https://artreview.com/the-museumification-of-queerness-queer britain-queercircle/

22. Mecca, Tommi Avicolli. “Gay Shame.” Alternet. 7 June 2002. https://www. alternet.org/2002/06/gay_shame

23. Office for National Statistics (ONS), released 6 January 2023, ONS website, statistical bulletin, https://www.ons.gov.uk/

peoplepopulationandcommunity/culturalidentity/genderidentity/ bulletins/genderidentityenglandandwales/census2021#cite-this statistical-bulletin

24. Oladiop, Gloria.”Influencer Dylan Mulvaney condemns Bud Light’s response to transphobia.” The Guardian, 29 June 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/jun/29/dylan-mulvaney-bud-light-transgender

25. Pablo Expósito-Campos, “A Typology of Gender Detransition and Its Implications for Healthcare Providers” 2021. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 47:3, 270-280, DOI: 10.1080/0092623X.2020.1869126

26. Pedroni, Laurence. “Selling Queer Rights: The Commodification of Queer Rights Activism,” Themis: Research Journal of Justice Studies and Forensic Science: Vol. 4 , Article 2. 5 October 2016.

27. Searle, Adrian. “Queer British Art 1861 - 1967 review – strange, sexy, heartwrenching.” The Guardian. 3 April 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2017/apr/03/queer-british-art-review tate-britain

28. Serafinowicz, Sylvia. “Queer British Art 1861 – 1967” ArtForum, Vol 56. No. 2. October 2017. Available at: https://www.artforum.com/print/ reviews/201708/queer-british-art-1861-1967-71281

29. Siegel, Jonah. “Owning Art after Napoléon: Destiny or Destination at the Birth of the Museum.” PMLA, vol. 125, no. 1, 2010, pp. 142–51. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25614443. Accessed 7 Jan. 2023.

30. Stankard, Mark. “Andy Warhol; Children In Mind?” New York Times, 28 July 2002. https://www.nytimes.com/2002/07/28/arts/l-andy-warhol children-in-mind-166545.html

31. Street-Porter, Janet. “The Tate Gallery is wrong to put on a ‘queer’ art exhibition.” The Independent. 22 April 2016. https://www. independent.co.uk/voices/tate-gallery-wrong-put-on-queer-art exhibition-a6996351.html

32. Tate Britain. “Exhibition Guide: Queer British Art 1886 – 1967.” Tate. 2017. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/queer-british-art-1861-1967

33. Umberson, Debra. “Texas Professors Respond to New Research on Gay Parenting” HuffPost, 26 August 2012. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/ texas-professors-gay-research_b_1628988