Sour-Puss: The Opera - Shame, Queer Play and Melancholia 🧪🐱

It’s been over a month since I spoke to Artist and Psychotherapist, Jessica Mitchell. We met for the first time on Instagram live at the beginning of March, where I interviewed Jessica following her participation in the Round Lemon X Shout exhibition, with her drawings ‘Oscar Wilde’, ‘I hear you’ and ‘How Come?’ displayed in the metaverse. Mitchell gave us an insight to her artistic process when creating work, her relationship to fellow exhibitor and image maker artist Diogo Duarte, and the product of their co-collaboration, Sour-Puss: The Opera, published by GOST Books with a contribution from curator Anna McNay. It’s a curated culmination of drawings and images, partly contextualised by text.

Jessica and Diogo’s baby – Sour-Puss: The Opera – is the product of 5 years of collaboration. I’m introducing their book as their ‘baby’ to echo how Jessica Opens the text ‘On Friendship and Collaborating with a friend’:

“It’s a funny thing to make a baby with someone you aren’t having sex with, but that is what creating Sour Puss: The Opera has been like for me”

I caress their baby in my hands. I stroke the texture of her hot pink satin cover with my thumbs as her slippery surface is suddenly disrupted by a slightly stickier one. I tilt the baby in circular motions with my wrists so that the light captures the cornered embellishment of the printed illustration. Two red claw-like hands (or feet) stretch across the centre of the cover, just about distinguishable enough from the raging pink backdrop. My eyes are toying between the vivaciously seductive pink and the subtly, yet almost aggressive and traumatic imprints of red. They say never judge a book by its cover – but I’m already bewitched by this one.

I turn her first page where my eyes meet an abyss of green. I’d describe it as a forest green, or perhaps emerald green; quite the cooling and calming contrast to her hot fiery exterior. It feels as though I’m at the beginning of an intimate journey, yet blissfully unaware of its significance.

I turn another page where a variety of shapes and colours collide in a multidimensional felt tip mania. Geometry spans through every element of the page, not only in its deliberate triangular rhythm, but also through the ghostly faint lines in the background. It feels like a doodle in the back page of a schoolbook. The backdrop of the paper’s linearity evokes an educational nostalgia, and the disruption of its uniformity in turn provokes a sense of queer playfulness.

This queerness leaks onto the next page as the ink literally seeps through to the back of the previous page - an encounter with the ‘other’ side of the drawing. I interpret this as a nod to the permeability of Sour-Puss, as Diogo describes her as ‘a creature of extremes in pursuit of connection in a seemingly unusual way’. As far as we know, her fleeting colours and conflicting emotions are central to her being. She’s somewhere between fictional and real, but her characteristics also occupy this liminal state. She’s not afraid to transcend conventional boundaries. There are three sets of these permeable felt tip drawings – a hidden triptych (or maybe even a heptatych if you’re counting the ‘other’ side) – before we encounter the Opera itself.

The series of the 32 photographs taken by Image maker Duarte undoubtably conveys a journey, or as Jessica describes, ‘a fantasy coming out story’. It’s a surrealist tale using Jessica herself as the subject, navigating through layers of melancholia, shame, visibility and acceptance. The photographs encompass a putative leakiness throughout, as my eye leads me through the series towards a metaphorically symbolic green ‘staining’.

The visibility of the stain is stark; right from the first image through to the very last. It’s queer, ‘other’, and most completely abject - as observed by Curator Anna McNay in her short essay ‘Shame and the persistence of the stain: Sour-Puss, the Frankenstein Daughter’. McNay draws parallels from this staining to Kristeva’s ‘Powers of Horror’ as the stain itself occupies a liminal state of matter between being a liquid and solid, provoking a feeling of ambiguity and unease, and in turn, infiltrating the viewer with this feeling of abjection. It’s this, paired with the notion of Sour-Puss as ‘cast off’ from her mother which forms Sour-Puss’ own abjected ‘self-conscious gaze’.

“from somewhere, [Sour-Puss] emits a staining fluid, which worsens the more visible she is made”

The stain is explosive, unpredictable and persistently present. As I move through the images, it bursts uncontrollably. It seeps through the surfaces of an empty shower room, green energy bouncing and refracting from the walls with only Sour-Puss’ trademark pale pink blouse remaining: a trace, relic, or carcass of a shedded skin. Here, Sour-Puss is transformative.

The stain permeates through skin. It’s completely intrinsic to the body. Even when Sour-Puss attempts to hide in the dark, she can never evade the sunlight creeping through the curtain to expose her coughed up green phlegm, or the confrontation of the mirrored halo light exposing her green rash-like bodily staining. In one of the images, the stain is literally ‘the chip on [her] shoulder’: a punitive burden and grievance.

Then comes a turning point. I think that it’s the image where Sour-Puss sits at a gloss black table in her blush pink blouse as she toys with her hands. There’s a symbolic transaction in the form of her hand gesturing as if she’s passing something from one hand to the other. She’s isolated under an intense spotlight as if she’s in questioning at a police station. It’s a moment of true contemplation for the first time, as she comes to terms with her own sense of self - her gesture symbolically mirrored through the reflected surface of the desk.

Following this turning point, Sour-Puss is reborn. She exchanges shamefulness for playfulness, holding our gaze through a wild cornfield, exploring her true self in becoming naked.

It’s at the end of this photographic series that we feel a real 360 degree moment, as Sour-Puss has emerged from a dining table towards another dining table. Although that being said, these images feel as though they’re Oceans apart. Whilst the first image feels vacant (echoed through her empty plate and downward gaze), the final image is bursting with vibrancy. Sour-Puss is embodying what was once a shameful green stain as part of her everyday wardrobe in the form of a green vest top - proud, accepting and content.

We’ve journeyed through Sour-Puss: The Opera as Diogo describes ‘like a phoenix rising’. Now that we’ve experienced shame, joy, pain and so many other emotions, we turn to the text - sandwiched by a compilation of Jessica’s drawings. The text acts like a dialogue as it’s written by both Jessica and Diogo who are each revealing their personal perspectives on the creation of Sour-Puss. However, they’re in fact short monologues intersected between one another to form a type of non-conversation which just feels conversational.

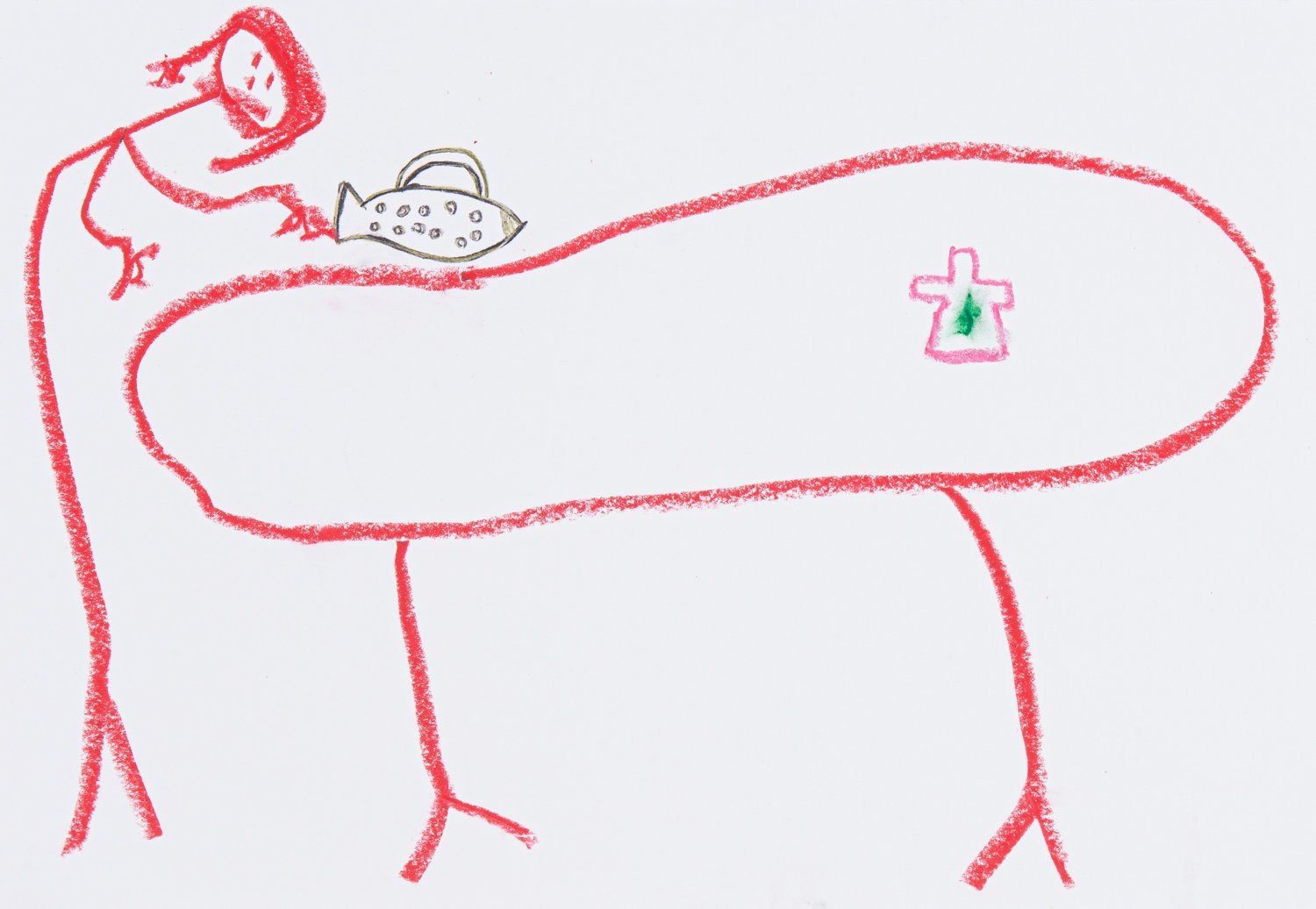

Jessica’s style of drawing is childlike - a derivative from the curious and playful attributes of Sour-Puss herself. There’s an innocent exploration of her own sexuality and body through spike-like piercing nipples, frustrated scribbles and surrealist-like scenes. Her expansively imaginative ‘fertile valley’ drawing is one of my personal favourites: It’s like lesbians rewrote the creation story, the page bursting with colour and new life whereby ‘she and I create this with our sex’.

I could almost view each medium of Sour-Puss: The Opera (the drawings, the text, the photographs) as separate bodies of work – just exhibited in interconnected rooms of a shared gallery space. Each of the mediums have personalities of their own, yet they also feel connected, constantly informing each other and belonging intrinsically to one another.

Part of me wants to view the Opera as one permeable mess of things rather than such perfectly curated mediums which are isolated from each other. Would the meaning of the photographs change if they were layered with drawings and text extracts? What would this look like on the page? Would the feeling of the work encompass more fluidity rather than connections between the shifting of different mediums? Nevertheless, It’s a curated body of work both deliberately foreboding and surprising.

As I draw this review to a close, I just want to make it clear that there’s so much more to discover about Sour-Puss: The Opera beyond my investigation of it; Journeying through all 32 images rather than just a small selection, the non-conversational conversation between the collaborative duo which serves true testament to their relationship – including the insightful analysis of the male gaze wrapped with Anna McNay’s perspective on it all.

So, who exactly is Sour-Puss? The Frankenstein Daughter, a composite character, an extreme hybrid manifestation of Jessica and Diogo’s relationship? Even her co-creators are still unsure. Whoever she is and has become[ing], the creation of Sour-Puss was above all ‘an exercise in hope’ for Jessica and Diogo, and her story feels so tangible to us because as McNay concludes: ‘Sour-Puss: The Opera is a lesson in living life’.