Is it fair?

Part 3 of ‘Mind Stretching’: a series aiming to debunk game theory concepts, whilst encouraging you to expand your creative horizons.

Do your friends and family reach the same conclusions when it comes to fairness as you do every time? How about your wider community? How about country-wide? Why don’t we all have the same compass when it comes to fairness? What is fairness, who decides what is it, and how?

What is acceptable as fair around the globe will differ. Fairness also fluctuates over the centuries.

The Talmud is an ancient document that represents the origin of Jewish law. In it, we find a story of a man who goes bankrupt, and his creditors need to reclaim more than he had left when declared bankrupt.

The man owes 100 coins to creditor number one, 200 coins to creditor number two and 300 coins to creditor number three.

If the man would’ve had 600 coins, he could’ve paid his debt in full and every creditor would’ve been happy. But what happens when the man has less than what he owes by various degrees?

The book presents us 3 hypothetical situations:

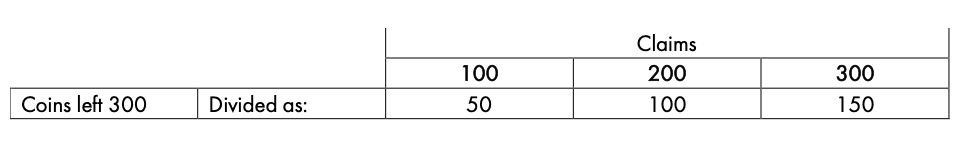

A. The man has 100 coins left that need to be divided between the 3 creditors.

The book is recommending for the 100 coins be divided as follows:

Every creditor gets the same number of coins regardless of the amount they lent. This is a socialist distribution; everyone gets the same pay out regardless of the amount they are given.

Is this fair? Sure, if you ask creditor number 1; how about creditor number 3? How likely will creditor number 3 be to lend out larger amounts of coins in the future?

B. The man has 300 coins left that need to be divided between the 3 creditors.

The book is recommending for the 300 coins be divided as follows:

Every creditor gets back half the money they lent. This is a proportional division - each of them recovering 50% of their money. This is probably closer to what we would consider fair today.

Both of these divisions are easy to understand as they seem intuitive and have a simple formula. But the third example, when the man owes 200 coins, is a bit strange.

C. The man has 200 coins left that need to be divided between the 3 creditors.

The book is recommending for the coins to be divided as it follows:

Why like this? Maybe the Jews were not very good with fractions thousands of years ago. Or maybe they enjoyed giving each other a good puzzle.

There is a logic to this division. In fact, the formula that the Talmud is recommending as being the fair way to pay your creditors respects all 3 situations.

If you can’t see the formula straight away, don’t worry. Many scientists struggled to understand the logic of this division until the 1980s when professors Robert J. Aumann and Michael Maschler published an article elucidating the mystery. And they only found a reliable algorithm because they studied other situations. The above information is insufficient to reach a valid conclusion.

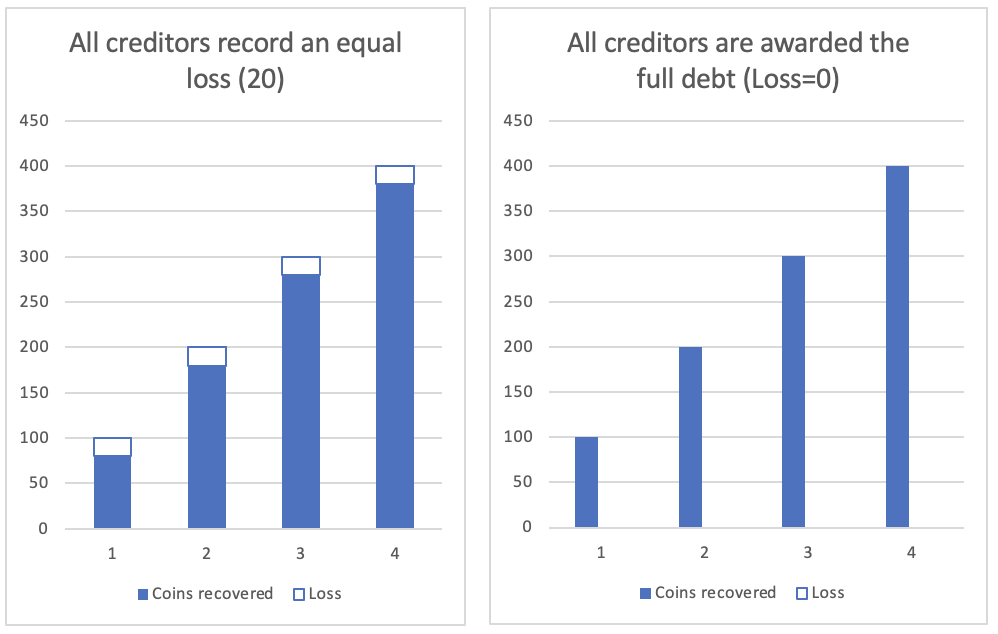

For them, fairness meant “equal division of contested sum” – sounds fancy but it just means a judge would divide equally the sum reclaimed by all creditors following a pattern we are about to explore.

To understand this method easier, let’s look at a situation where there are only 2 creditors.

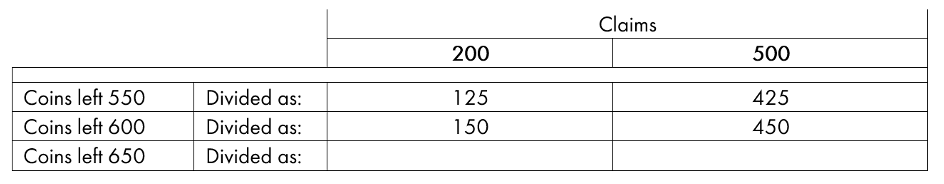

If 2 creditors are claiming 50 and 100 coins, and the person going bankrupt only has 100 coins left, the sum of coins contested by both creditors is 50. The other 50 are only contested by the second lender. So, the first 50 are equally divided between the two and the result would look like this:

They both register a loss of 25 coins.

Situations like this can be resolved in 3 simple steps:

1) Identify the claim made by both parties (50)

2) Divide it by 2 (25 & 25)

3) Allocate the undisputed sum to the highest lender (50 coins go to the second lender).

Simple, right? To clarify, let’s have a look at a series of examples:

When the lender has up to 500 coins left, the formula is a simple 3-steps process.

When the lender has 500 coins left, each lender records a loss of 100 coins.

But when the loss becomes equal, the formula introduces another rule. The lender of the lowest amount should not record a loss greater than the other lender(s). Thus, each remaining quantity left after the losses have been matched will be equally divided between the 2 as follows:

I know you managed to fill in the two empty cells, well done!

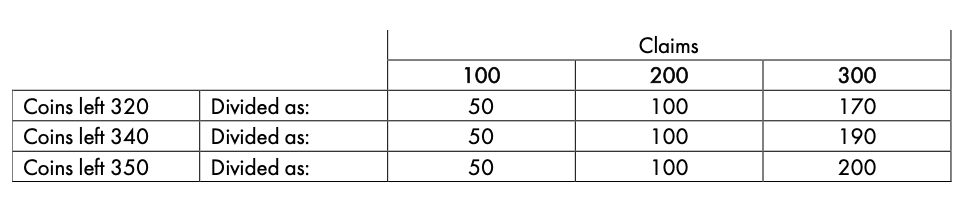

When there are 3 or more lenders, the logic will be the same but a bit more longwinded. And the rules will be:

1) Organise the creditors in ascending order.

2) Divide the sum claimed by all until the lowest lender reaches half its claim.

3) Continue the division until the next creditor reaches half of its claim. The first creditor’s loss remains at half of its lent sum.

4) When the second creditor reached half of its claim, carry on until all of them reached the halfway mark.

N.B. this rule uses the expression “all of them” because the rule can be applied to more than 3 lenders.

5) After each lender reached the half-mark point of their loss, the rule alters one more time. The highest lender will start claiming coins back until its loss will equal the loss of the second highest lender.

*Both highest lenders record a loss of 100 coins

*The first lender records a loss of 50 coins

6) Continue to divide the coins until the loss recorded by the two highest lenders matches the loss recorded by the first one.

*All three lenders record equal losses (50 coins)

7) Carry one ensuring they all record an equal loss.

If this division is a bit unclear, the following visual representation should help.

To make things more interesting, let us introduce a fourth lender. This fourth lender is owed 400 coins. And let’s repeat the rules mentioned above:

1. Organise the creditors in ascending order.

2. Divide the sum claimed by all until the lowest lender reaches half its claim.

*The first lender reached its halfway point (50 coins).

3. Continue the division until the next creditor reaches half of its claim. The first creditor’s loss remains at half of its lent sum.

*The second lender reached its halfway point (100 coins).

4. When the second creditor reached half of its claim, carry on until all of them reached the halfway mark.

Imagine these are water bottles and you carry on filling them half full from left to right.

If there are more than 4 creditors, this step will be continued for however many creditors there are.

5. After all lenders reached the half-mark point of their loss, the rule alters. The highest lender will start claiming coins back until its loss will equal the loss of the previous highest lender.

6. The coins will be awarded to the highest lender(s) until the loss recorded by the highest lender(s) matches the loss recorded by the one before them.

You can imagine we are now filling in the bottles from right to left until all of them have the same empty space.

7. Carry one ensuring they all record an equal loss.

Is this the fairest way of reclaiming debt? Definitely not the simplest.

Now that your mind was stretched a bit, you can contemplate a more simple concept – fairness.

Generally, when aiming to achieve fairness, society looks at what was agreed upon previously.

This is the temporal aspect of fairness. We respect the precedent. Do we think our predecessors were somehow wiser? Or is it done out of complacency? It is easier to rely on conclusions already reached by others?

Is this because we want to be consistent with what was agreed upon previously? Is consistency vital for fairness? If so, why did the Jews stop repaying claims following the formula above? At some point, they decided to discard it – and break the consistency criteria. So, throughout time, when society changes, our perception of fairness changes.

Because it would be very demanding & time-consuming, we refer back to previous cases when we need to evaluate what is fair and what is not… and, generally, this is a reasonable decision because other people have spent an awful lot of time to reach those conclusions. Also, because there was a precedent, society is more likely to accept similar decisions on related matters. But what if the ones before us were biased, what if their interests conflicted with what is equitable? What if they knowingly or unknowingly missed some aspects of the problem? Or what if nowadays there are more factors to consider when evaluating fairness?

Transparency should also be a characteristic of fairness. This way when people are taking decisions, it increases the level of predictability. We’re also reassured that each of us receives the same treatment. But what about the cases when receiving the same treatment would be unfair? If our contribution to a goal is more (or less) than our team members, should we receive the same reward? And how and who decides what is what?

Just as well, transparency should be questioned. I struggle to find a situation where transparency would count as unfair – but, nevertheless, I question it. Because it is healthy to question fairness. Can you think of a situation where transparency would hinder fairness?

The way a community defines fairness influences how the people from that community take decisions and, implicitly, how that community evolves. Our society’s policymakers have a huge impact on our lives. Notice what civilisation looks like in the west compared to the east. To what extent do you think our perceptions of fairness played a role in this?

When should we accept the precedent & status quo as good enough, and when should we fight the norm?