I Felt That: An Exhibition On The Gender Pain Gap

I Felt That (30th June – 3rd July 2022) at The Tub, Hackney

For International Women’s day 2023, I’m revisiting an exhibition from the summer of 2022 called ‘I Felt That’. Even though this exhibition has been and gone, I am writing this piece in the present tense. I approached ‘I felt that’ by [with]nessing the experiences of these artists - their traces of pain embedded, memorialised and encapsulated in their work as a distinct emotive feeling. This reflection attempts to convey my experience of this feeling in the most authentic way possible.

About ‘I Felt That’

Nestled in the London borough of Hackney down Broadway Market Mews lies ‘I Felt That’: an exhibition at artist-run project space The Tub. Echoing behind the Tub’s giant red doors are the collective voices of thirteen Women and Non-Binary artists seeking to dismantle the patriarchal imbalances of gendered pain. ‘I Felt That’ is a community where ideas are shared, developed and nurtured as a collective through talks, workshops and wider discussion, whilst also allowing room for artistic autonomy and individualism. This hybrid exhibition-collaboration approach developed by Curator Joséphine-May Bailey is care-centred at its core, allowing artists the safe space to exchange lived experiences of the gender pain gap, whilst feeling both emotionally supported and artistically stimulated.

There are often slippages and crossovers in the artists’ personal experiences of pain. Whilst throughout this essay I have grouped artists together to talk about specific pain points – menstrual, post-natal and chronic pain - this is by no means exhaustive of gendered pain points, nor definitive of an individual’s experience of the gender pain gap (e.g. A non-binary mother with chronic period pain and a post-natal depression diagnosis will have a different experience of the gender pain gap to a woman with undiagnosed chronic back pain and no children. But these two individuals both suffer from the gender pain gap and would probably find common ground with their experiences of chronic pain).

Menstrual Pain

Despite being a pervasive and recurrent phenomenon for women, menstrual pain is too often normalized in our society. Mhairi Bell Moodie and Louise Benton both use sculpture to challenge the role of women and non-binary people conforming to societal expectations and discreetly carrying the burden of coping with period pain.

“80% of Women experience period pain in their life.”

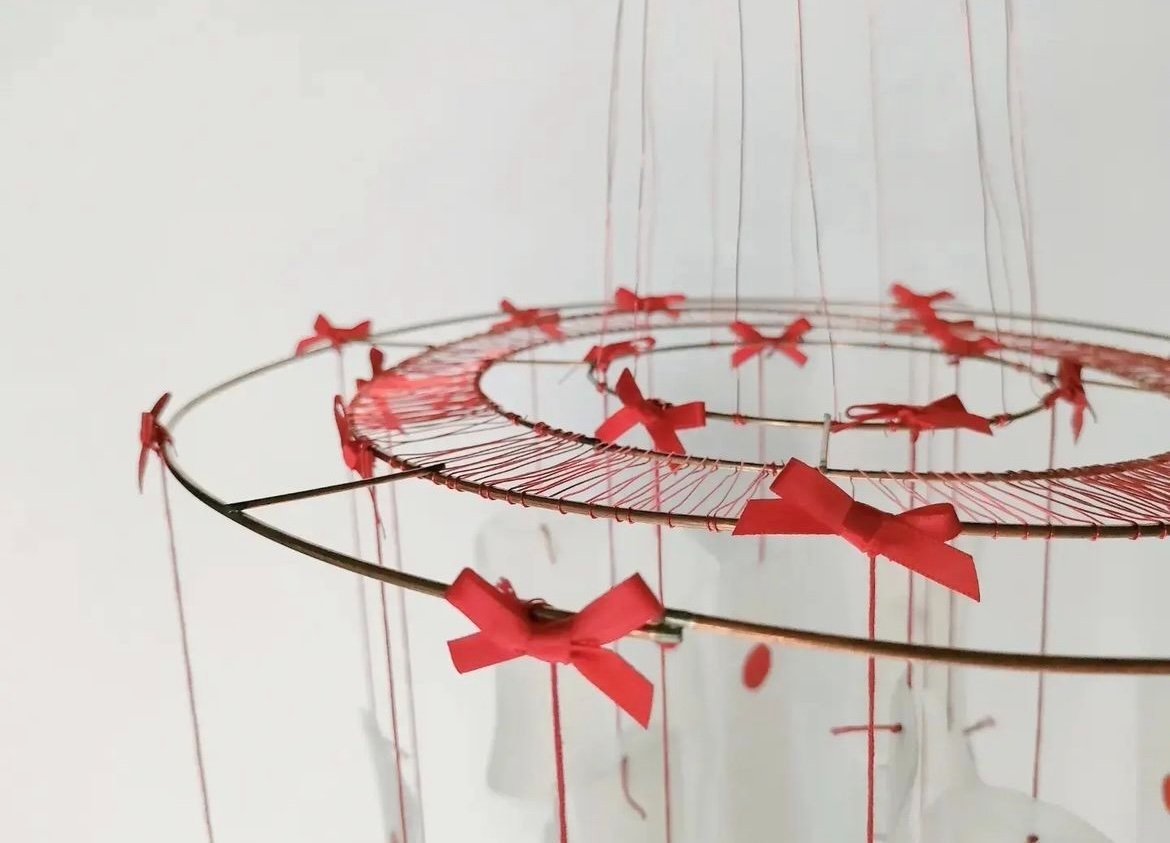

Mhairi Bell Moodie’s ‘Your Calendar Is Wrong’ sheds a light on the issue of patriarchal medical neglect when it comes to menstrual pain and the emotional toll it takes on women. Whilst in conversation with the artist, I was surprised to learn that this project was Mhairi’s first deviation from the medium of documentary photography, opting to play with ideas which were primarily driven by material instead. This ethereal sanitary mobile adopts a sculptural prowess which feels mature, each material signifying deeper reproductive politics. There’s so much to interpret from this work – from the tightly wound copper wire referencing the excruciating pain caused by insertion of intrauterine devices, to the red dot markers representing each day of Mhairi’s abnormal bleeding (also humorously commodifying the price of pain in an art market context). It’s also adorned in pretty red bows, suggesting the inherent sexualisation and objectification of female bodies.

‘Your Calendar is Wrong’ by Mhairi Bell Moodie

Mhairi critiques that the 12-month Calendar is not designed for Women, suggesting that a 13-month cycle bound of 28 days would make a lot more sense. ‘Your Calendar Is Wrong’ has a dual nature. It protests against the make-up of the 12-month calendar as we know it, whilst also considering the entrenched patriarchal fear of women ‘exaggerating’ their own reproductive health issues, dismissing what might be stereotypically deemed as a ‘Woman’ problem.

‘The Twelve Labours’ by Louise Benton

Louise Benton critiques the falsification of sanitary advertisements through her aesthetically feminine ceramic ‘The Twelve Labours’. It’s a parody which subverts the tale of the twelve labours of Hercules, instead using satire to demystify the smokescreen of hyper-active fearless women through the lens of artistic male methods of storytelling. Louise highlights just how damaging this inauthentic image of the ‘unstoppable woman on her period’ actually is, as it not only evokes resentment from women who might suffer painful menstrual conditions such as endometriosis and dysmenorrhea, but it also inflicts shame and guilt on women who aren’t physically capable of carrying on with their normal routine whilst menstruating. It also poses many social pressures, holding up unrealistic expectations of women through the lens of a man, who will expect them to ‘deal with it’, because if periods are commodified as pain free, then surely this means they are pain free, right? Louise’s playful handling of pink and red shades blurs the lines between aesthetic feminine stereotypes and bodily fluids, rendering the work as both alluring and abject.

Post-Natal Pain

Few women and non-binary artists in art history have made work about motherhood - take the likes of Alice Neel, Carrie Mae Weems, Kathe Kollwitz and Mary Kelly for example. But even more scarcely explored in art are the mental health ramifications of becoming a mother. Ruth Batham and Lucy Cade are two artists who are breaking this barrier.

“Between 10% and 20% of women develop mental health problems during pregnancy or within a year of giving birth… Around 50% of perinatal mental health problems are untreated or undetected.”

Ruth Batham’s ‘(Non) Textbook Bodies 32022’ magnifies the complex and often overlooked relationship between childbirth and post-natal depression. Swimming across the gallery wall is a cut out of a baby, disassociated from her mother gazing outwardly beside her. The bodies both share the same colour palette - intensely warm tones of red, pink, orange, yellow and white bleeding into each other like marble. I notice the crumpled legs of the mother cut-out, exhausted and fragile, yet conveying her overwhelming strength and endurance. There’s a ghostly mirrored detail of two women on the breast area of the mother, like a trace of a past bodily memory. They’re outwardly evoking a sense of shock, with a tiny baby’s hand reaching upwards caressing her mother’s face – a subtle reminder of the child’s dependency. This multi-layered self-portrait evokes both tenderness and strength, the title itself protesting against motherhood being a process devoid of all mental feeling.

Justxtaposing Ruth’s warm tones with a breath of icy cool ones, Lucy Cade explores her personal experience of postnatal psychosis in her work ‘Bedside Manners’. The four blue canvases share a similar essence to Picasso’s intimate and dark ‘Blue Period’ paintings, but the gaze and posture of the subjects on Lucy’s canvas’ feel overly-glamourized for the contrasting clinical setting. She maintains a painterly daintiness that’s elevated by the dramatic backdrop of a draped blue fabric; on closer inspection I realise this is a hospital blanket. Through the blue tinted lens of the artist, we begin to grapple with the conflicting real and non-real in this frozen realm of psychological distress. Both artists convey surreal and powerful self-portraits as an entry point to acknowledge their experience of the serious mental symptoms of postnatal pain.

Chronic Pain

Frida Kahlo is the first woman artist who springs to mind when I think about the intersection of art and chronic pain. The haunting and surreal imagery in her works ‘The Broken Column’ (1944) and ‘Henry Ford Hospital’ (1932) are poignantly felt depictions of her life-long suffering with physical illness. But can you think of any women or non-binary artists who use their work to challenge gendered medical neglect and the lack of care for patients with chronic pain? Lavinia Harrington, Lucienne O’Mara, Shir Cohen and J Williamson are four artists who do.

“36% of women who experience and live with chronic pain said they didn’t think their health care providers took their pain seriously.”

Abstraction is the mesmerising form that Lavinia Harrington and Lucienne O’Mara use to translate their chronic pain. Lavinia Harrington sees her works “as maps, charting felt experiences”. Oils and soft pastels overlap and bleed into new marks; deep reds, pinks and purples ooze with synchronicity, generating a seductive bodily intensity. Echoing the title of the exhibition, her work ‘I Felt That’ is certainly leaking with viscerality. Harrington has endured chronic pain due to debilitating periods, acute pelvic pain and agonizing procedures, including a laparoscopy operation and helica treatment. Lavinia explains, “Enduring excruciating examinations and being repeatedly misdiagnosed led me to dissociate from parts of my body in order to cope.” Her drawings certainly show an inherent connection with colour, as well as an intimate embodiment of pain and endurance.

Lucienne O’Mara paints with a comparable level of intensity and viscerality, however, it’s texture that personifies her experience with chronic illness. Lucienne’s chronic illness has reframed the way in which she sees and experiences the world because her eyesight and depth perception have been altered. Imbued with gesture and movement, ‘Space Like Glass I Sit Quiet’ almost shifts between 2D and 3D, with impasto abstract-expressionist strokes brazenly sweeping across the canvas. Her use of text both grounds and frames the visual abstraction to a particular feeling: the feeling of having to conjure patience whilst being repeatedly dismissed and neglected by male doctors. “It seems to be a familiar story to most of the women in this group unfortunately,” she comments.

J Williamson and Shir Cohen both use sculpture and installation to challenge historical prejudices of women and gender non-conforming individuals in medicine. These prejudices continue to be experienced today. J Williamson sculpts a green ritual site evocative of the spiritual or occult in ‘Layered Forms’. Conkers lie in a ceramic dish swimming in mysterious juices, whilst a slumped marbled bodily form evokes a sacrificial body part, and broken ceramic vessels appear to collapse and melt into each other. It’s a site that seems deeply connected to mother earth and nature through both medium and context, reforming and re-casting healing objects against historically gendered prejudices. The artist explains, “Many medical prejudices that come from history were based upon men’s feelings, yet women’s own feelings about their bodies were/are seen as weak, false or hysterical.” This speaks to J’s personal experience of suffering chronic migraine attacks and debilitating menstrual cramps for the last decade.

Next to J’s work, I am struck by a harrowing depiction of a murdered frog. Its skin is shrivelled and discarded - almost as if it’s been trodden on - and a distraught and stain-like tearful facial expression is marked with red paint. The frog is a liminal being sprawled on its back, exposing two sets of genitalia. This soft sculpture titled ‘Mercifully Shot and Skinned’ by Shir Cohen reveals the medical bigotry inflicted on ‘othered’ genders that don’t fit the binary:

“The masculine ideal has been held as the standard throughout most of medical history and still is today in many ways. So anyone whose body physically differs from it is othered, and the more different they are, the bigger the impact is on their dealings with the scientific and medical establishment. This is further compounded by other oppressions, and so this group of people - which is most of the world - receive poorer care and are much more prone to be left in pain.”

I feel a great sense of urgency in these works - the demand for better chronic pain care and management for women and non-binary individuals is palpable.

The Spaces Between

Although I have outlined three instances of pain that are impacted by the gender pain gap – menstrual pain, post-natal pain, and chronic pain – it is important to note that these pain points are certainly not exhaustive, and there are numerous overlaps and intricacies between them. The other artists featured in 'I Felt That' explore gendered pain within the other fissures and crevices of this gap, and the spaces in between.

“Whiteness and maleness are silent precisely because they do not need to be vocalized. Whiteness and maleness are implicit. They are unquestioned. They are the default. And this reality is inescapable for anyone whose identity does not go without saying, for anyone whose needs and perspective are routinely forgotten. For anyone who is used to jarring up against a world that has not been designed around them.”

In Zayn Qahtani’s work ‘The Milk That Feeds The Soul Is Often Curdled’, a graphite drawing of a woman cradling herself in a foetal position takes centre stage. Adorned in a golden frame, she is cocooning herself with her luscious wavy locks, perhaps hiding from the world or protecting herself from harm. The title is a metaphor for lack of nourishment, and contamination of mother nature by patriarchal power structures. This exacerbates the gender pain gap, perpetuating oppression and generational pain, and leaving little room for growth for women and non-binary individuals, both spatially and metaphorically.

I see similar nuances in ‘I Thirst’ by Jennifer Nieuwland. A deflated sore breast hangs out to dry, melting in a surrealist fashion like Dali’s clocks in ‘The Persistence of Memory’ (1931). This breast serves as a corporeal emblem for motherhood, painfully pinched by a washing peg, strained of milk to its last droplet. There is so much to unpack in this singular image, from traces of domesticity to religious iconography. But what I find most striking is the intense pain conveyed by the tightly squeezed peg, revealing how bias and oppression persist in the most ordinary and mundane tasks in women's daily lives.

‘A Piercing Embrace’ by Polina Pak

Intertwining pain and comfort through her painting ‘A Piercing Embrace’, Polina Pak depicts a poignant memory shared by the artist's grandmother of getting her ear pierced for the first time. The image evokes the innocence of girlhood while examining the cultural expectations and gendered sacrifices imposed on women in the pursuit of beauty. This is further emphasised in the beautified setting of golden hair enveloping the figures, almost suffocating them within the confines of feminine beauty ideals. Despite the little girl's visible pain and swelling earlobe, she finds solace in her mother's embrace, highlighting the enduring nature of generational pain. I feel that this image challenges the notion that women should silently endure pain and instead celebrates the need for comfort and support within womanhood.

‘Trigger Warning: But I Never Saw Her Pray’ by Qingqing Liu

Qingqing Liu's performance, ‘Trigger Warning: But I Never Saw Her Pray’, incorporates the body as a material to explore the complex intersection of eroticism, fetishization, and traditional Eastern views on life and death. Drawing inspiration from 90's Hong Kong horror films, the performers are decorated in lace, bondage, and red mesh veils, evocative of a macabre underworld wedding procession. As the performance progresses, a haunting chorus of eerie and mournful wails reverberates throughout the venue, serving as a haunting critique of the inhumane treatment of women in contexts such as the one-child policy and the chained Xuzhou eight-mother child. Qingqing Liu illuminates the harsh realities of gendered oppression and exploitation, with her unparalleled artistic vision and evocative costume design leaving a profound and unforgettable impact.

Spoken-word poet Chloe LSH transforms a stanza from her moving poem into a tangible form, embodying the exhibition's theme 'I felt that'. White fabric letters subtly emerge from a white canvas - it’s difficult to read, but viewers are encouraged to engage with the work as if it were braille. I feel my way along the textures and read:

She moves forward, marvelling at all that is outside of herself. I stand back, smile and whisper “I feel that too”

Chloe's participatory approach is carefully conceptualized and thought-out. As more viewers interact with the work, touching and leaving their marks, it becomes more visible, allowing more people to 'feel' it on multiple levels. This sharing of words through touch and tactility reinforces the exhibition's overarching message of shared understanding and collective feeling of gendered pain.

It was a bittersweet feeling to leave the exhibition knowing that the artists had reached the course of their weekly sessions, and the project was drawing to a close. Joséphine has certainly created a lasting legacy in founding the ‘I Felt That’ group, cultivating new friendships and new perspectives on how we might respond to the gender pain gap.

One question is on the tip of my tongue – what are the artists doing 9 months later?

‘I Felt That’ lives on

Joséphine is now gallery director and curator of Pictorum Gallery in Marylebone – a contemporary art gallery focusing on women and POC artists and the nurturing of new talent. She has curated the gallery’s inaugural exhibition ‘Taking a Broom to the Wasps’ nest’, and more recently, ‘Between the Bridge and the Door’, as well as managing the PGL Incubating Residency, and flying Pictorum Gallery overseas to UVNT Art Fair in Madrid. Indeed, she has been very busy and continues to expand her growing legacy as a curator by shaping the careers of other incredible artists.

The footprint of ‘I Felt That’ continues to live through the artists in the show as Lucy Cade, Jennifer Nieuwland, Lucienne O’Mara, Ruth Batham and J Williamson are about to open ‘STRETCH’ – a group show with four other artists at Somers Gallery. The show is a conversation between artists who are all mothers, about what different stages of mothering feel like, and runs from 15th March – 25th March (PV on 14th March 6-9pm).

Zayn Qahtani also recently launched her debut solo show ‘Angels in Purgatory’ at Vitrine Gallery Fitzrovia. The show presents a new body of work exploring themes of destruction, resurrection and rebirth through a personal retelling of stories of the Nephilim, and is on until 8th April.

Polina Pak is part of a collaborative exhibition ‘Undusted Corners’ with Alexis Soul-Gray at Cromwell Palace, hosted by New Normal Projects. The show undusts and redefines new narratives around trauma, loss, and grief and runs from 8th-12th March.

All of the artists from the show will feature in the ‘I Felt That’ publication – made in collaboration with Ache Magazine, an intersectional feminist publisher on illness, health, bodies and pain. Featuring the artists’ works, Q&A’s, plus additional writing from Ache contributors, it’s a vital resource to elevate further conversation and art making on the topic of gender, illness and pain. Available to pre-order now and purchase from March 10th.

Bibliography

Artist Interviews Available to read: https://josephinemaybailey.com/ifeltthat

Criado-Perez, C. (2020) Invisible Women. 1st edition. Vintage Publishing: New York.

Healthy Women (2019) Executive Summary of Healthy Women’s Chronic Pain Survey [pdf] Available at: https://roar-assets-auto.rbl.ms/documents/6876/Chronic%20Pain%20Survey.pdf

Mental Health Foundation (2022) Mums and Babies in Mind. Available at: https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/our-work/programmes/families-children-and-young-people/mums-and-babies-mind

Versus Arthritis (2017) Chronic Pain in England: Unseen, Unequal, Unfair [pdf] Available at: https://www.versusarthritis.org/about-arthritis/data-and-statistics/chronic-pain-in-england/

Women’s Health Concern (2022) Women’s Health Concern Factsheet, Information for Women, Period Pain [pdf] Available at: https://www.womens-health-concern.org/help-and-advice/factsheets/period-pain/