Art & the digital Revolution.

Part 1 - How has social media redefined the context of how we see, understand and engage with art?

Abstract

‘Modernity (...) does not occur without a shattering of belief, a discovery of the lack of reality in reality - a discovery linked to the invention of other realities’ (Lyotard in Mirzoeff. 1999: 7).

Social media catalyses culture, creating new cultures and social standards in its wake. It does not remain static, but scatters among the physical and among the digital.

In the wake of social media, specifically Instagram, how is art relevant today? Can we understand art amongst the digital cultures of daily online life?

Photography is a part of daily human existence, and in art, photography focuses on such experiences. We are surrounded by the everyday usage of photography; it is paralleled by photographic art, but can photography be art in terms of social media?

Throughout this essay I want to interrogate the question: how has social media redefined how we see, understand and engage with art?

Introduction

Art and the cultures of social media, specifically seen in photography, run closely beside each other. They emulate the language and visuals of each other, honing into the everyday aesthetics of human experience.

Through art we discover the digital, we digest and understand it. Through the digital, we try to discover and understand it.

And so it seems that here, ‘art, [the digital] and human existence have become the same thing’ (Nash. 2017: 113).

On social media, we see art in the context of everyday digital cultures, and yet, social networks offer a lack of context for art (Tromoel. 2013: 10); leaving artworks in a stasis on these platforms, left to be ravaged by the digital eye. Can art be art in a social sphere which offers no institutional declaration of an art context?

Photography suffers from this lack of a contextual declaration. With the growth of photographic based social media platforms like Instagram, it is hard to separate domestic photography from photographic art. The two continually mimic each other, reflecting on the aesthetics of art, as well as the aesthetics of the everyday.

To what extent has social media redefined the context of how we see, understand and engage with art?

Chapter 1: Art After the Digital Revolution.

‘And thus the Capitalist System came into existence, and with it the thing we call ‘culture’ (Read. 1963: 12).

Digital culture encapsulates the human experience of the everyday on the internet. In my use of ‘Digital Culture’, it closely references social media platforms, such as Instagram, which came into existence in 2010. These platforms exhibit microcosms of culture through curated realities resulting in a relative fiction. ‘We can no longer talk of technology as if it were separate from, or even an extension of, humanity’ (Nash. 2017: 112).

It is no secret that humanity plays out their lives online; where existence in the physical world and the digital are blurred. ‘Human existence has literally become a formal, abstract system, which we all call the digital’ (Nash. 2017: 113). These blurred boundaries are the same for art online; as ‘art and human existence have become the same thing’ (Nash. 2017: 113).

So, what is culture? Culture is defined by one’s very being, it is organic; if one, a society is free, ‘then culture will be added without any excessive striving after it’ (Read. 1963: 30). For me, two types of culture emerge here: those we define by tradition and stereotypes and, a series of cultures defined by our very being and behaviour, generally seen online with our experience of digital technology.

Digital culture cannot be defined by a single word or phrase; it is simply the way human life culturally plays out online.

Art, in a multitude of ways, struggles with the digital world, because art largely loses its meaning online in the void of the internet, as it cannot be judged or assessed by the traditions of physical space (Tromoel. 2013: 10). Essentially ‘art must be placed in a context that declares it to be art’ (Tromoel. 2013: 10) - and does the digital world suffice?

Yumna Al-Arashi discusses how her practice loses its contextual meaning on social media in the colloquial publication ‘Mixed Feelings’ (2019). She, like Tromeol, highlights the lack of context in the online word, where ‘at times the objective of my work completely disappears when I share it,

leaving instead the sad skeleton of a love killed by the outside world’ (Al-Arashi in Shimada and Raphael. 2019: 66). Specifically when concerning her work, the online world and media ravages it to support and share their own ideas about Islamic culture and religion. Al-Arashi’s work explores Muslim culture and religious practice in contemporary culture (see Figure 1). Due to modern attitudes of Islamophobia in the West it is clear how Al-Arashi’s work could be used for specific agendas within the news and on social media. ‘We’re merely exploiting [Islamic women] to attract clicks for a Capitalist gain - and this just divides us further’ (Al-Arashi in Shimada and Raphael. 2019: 65).

Figure 1

Nicholas Mirzoeff, attempting to define ‘Visual Culture’ in the beginning of the digital age, circles around the notion that ‘modern life takes place onscreen’ (1999: 1) before the existence of platforms like Instagram that unfold the everyday ‘perfections’ of human existence and experience. With such ‘digital cultures’ emerging, a flurry of imagery arises across digital spaces; where we live among the digital, always visualising the real. ‘Modern life’ does ‘take place onscreen’ (1999: 1), where the lines between the physical and digital blurs, forcing individuals and artists to question reality in the digital world.

Figure 2

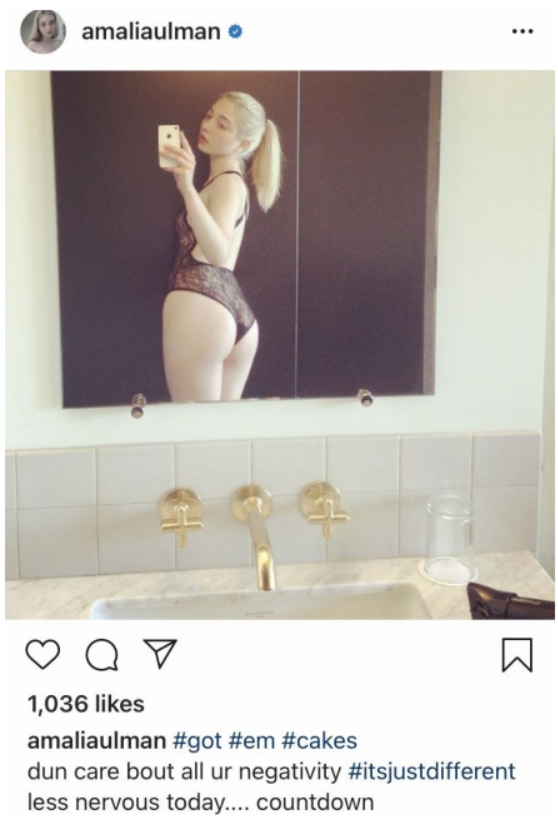

Amalia Ulman answers this question pertinently in her performance piece ‘Excellences & Perfections’ (2014) - also known as ‘If you don’t pay my bills’. The work drives a conversation about the culture and aesthetics of these online platforms; playing to a specific dialect adopted by Instagram users (see Appendix 1). She drives this by tackling the conflict of fantasy by ‘bringing fiction to a platform designed for “authentic” behaviour’ (Ulman in NYT. 2017).

Through this work, Ulman exposes the curatorial aspect of the platform, creating imagery purely for Instagram; again where this essence of reality and fiction blur. She utilises specific digital cultures to create a faux reality in the performance by using ‘fiction with a language that was natural to that space’ (Ulman in NYT. 2017).

Figure 3

So why should we create and be interested in a work that discusses the everyday cultures and aesthetics of Instagram?

‘Excellences and Perfections’ exposes our innate desire to consume; where such ‘influencers’ become vessels for consumerism; living advertisements for certain capitalist beliefs. Social media, as we have already established, blurs the line between fiction and reality; as much as it merges advertisements and genuine thought. Many of these ‘influencers’ act as an accessory to consumerism; preaching and sharing products by depicting everyday aesthetics.

Figure 4

So, why are we so concerned with the everyday aesthetics in art and online? When discussing ‘everyday aesthetics’, we must first define what we mean by such a term. Pioneered and coined by Katya Mandoki in her publication ‘Everyday Aesthetics: Prosaics, the Play of Culture and Social Identities’ (2007), the term explores the aesthetic nature of human experience; mostly referring to the beauty of everyday life while also liberating aesthetic inquiry from a consistent appreciation and focus on aesthetic beauty (Saito. 2019). The majority of writing concerning ‘everyday aesthetics’ derives from ‘John Dewey’s Art as Experience’ (1934) (Saito. 2019), however, Mandoki was the individual to coin the term. Specifically Dewey highlights how aesthetic experience can and does occur in the workings and daily practices of life.

What does ‘everyday aesthetics’ mean and refer to in contemporary visual culture? Kawauchi encapsulates extraordinarily well the aesthetics of the everyday, see Figure 5; where her practice visualises the ‘pleasures and terrors of everyday life (...) revealing both a feeling of beauty and a sinister tone’ (Parr. 2004: 22).

Figure 5

Kawauchi’s practice visualises the mundane of everyday human experience; whether this is an appreciation of the beauty of human life, of the ‘negative’ or rather ‘ugly’.

When we discuss “everyday aesthetics” we are discussing the home, the workplace, places of leisure and entertainment (Leddy in Light and Smith. 2005: 3).The term refers to the ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ appreciation of our daily surroundings that Kawauchi clearly visualises in her practice.

Everyday ‘aesthetics has to do primarily with pleasure, and only secondarily with pain’ (Leddy in Light and Smith. 2005: 8). Here we reflect again upon Figure 5, imagery from Rinko Kawauchi’s dominant series ‘Utatane’. Referring back to Martin Parr in the British Journal of Photography, in

Kawuchi’s practice, we do experience the pleasures of the everyday; yet always accompanied or followed by a sinister appreciation or experience of human existence (2004: 22). So indeed, we can see here that “everyday aesthetics '' in visual culture and art are primarily to do with pleasure and secondarily to do with pain, see Figure 6.

Figure 6

In art, we see everyday aesthetics appear time and time again; throughout performance pieces, photography, painting and video; ‘we see art (...) in terms of everyday aesthetics, and we see everyday aesthetics (...) in terms of art’ (Leddy in Light and Smith. 2005: 4). We may believe that the aesthetics of art is incompatible with everyday aesthetics due to the history and traditions of art; but in fact, art is affected visually and aesthetically by the continuity of human experience. It is art that concerns us with our aesthetic experience of living; that encourages us to perceive our cultural qualities. After all, it is the ‘constant viewing of contemporary art [that] helps us appreciate our everyday environments’ (Leddy in Light and Smith. 2005: 19). So in this sense, art’s concern with everyday aesthetics encourages the individual to visualise the aesthetics of their private lives.

Figure 7

Amalia Ulman’s performance piece ‘Excellences and Perfections’ is a product of this consistent concern and visualisation of everyday aesthetics on social media, where here ‘we see art (...) in terms of everyday aesthetics, and we see everyday aesthetics (...) in terms of art’ (Leddy in Light and Smith. 2005: 4). She questions the language and discourse of everyday aesthetics in the online world; so too does Erik Kessels with ‘24hrs in Photos’ (2011).

Figure 8

Erik Kessels questions the reality and discourse of the online world; driving a conversation on the ‘overload of images’ (Kessels. ca. 2020) of private everyday aesthetics that we see on social

media. Using the digital platform Flickr, Kessels created the work ‘24hrs in Photos’ (2011), printing 350,000 “found” images uploaded in a 24 hour period. Throughout the flurry of images, we are generally confronted with very personal everyday imagery, tackling ideas of visual culture in the digital world, where ‘the visualisation of everyday life does not mean we necessarily know what it is we are seeing’ (Mirzoeff. 1999: 2). Kessels drives a conversation about human detachment from photography; where although we can see an image as Mirzoeff discusses, it doesn’t mean we necessarily we understand what we are seeing (1999: 2)

Figure 9

This work does not rely on photography itself; a still medium, but rather the acceleration of culture online; ‘visual culture does not depend on pictures themselves, but the modern tendency to picture or visualise existence’ (Mirzoeff. 1999: 5). It is this drive to capture the aesthetics of everyday life, purely to be shared online which is the culture itself.

Art too relies on this tendency.

Figure 10

In Kawauchi’s case, she photographs the inexhaustibility of everyday human experience, much like individuals in the online world. Her work does not concern itself with cultural reproduction on social media and internet art platforms. Instead, she captures the very essence of life. through her fascination with the fleeting beauty of the natural world in relation to the human world; including also both birth and death. Her work across publications such as ‘Utatane’ (2001), ‘The Eyes, The Ears’ (2005) and ‘Illuminance’ (2011) depict the very same cultural reproduction of mundane human experience that we come into contact with on Instagram, essentially this microscopic view of everyday aesthetics.

Preceding many social media platforms such as Instagram, her work does not fall into such aesthetic categories; yet displays this constant scrutiny of human experience; the visualisation of everyday aesthetics. We see this today across the internet, where individuals are constantly concerned with their own lives and the perception of others. Was Kawauchi among this cultural revolution in art that pushed through the aesthetics of everyday life to be central to social platforms?

Figure 11

Instagram often mimics Kawauchi’s most prominent works; where ‘posts often appear as fleeting digital objects in a continually updated visual flow’ (MacDowall and De Souza. 2017: 9). The fleeting and temporal nature of life is captured in the digital world; mimicking what we experience in reality, again blurring this sense between the physical and the digital; ‘human existence has literally become a formal, abstract system, which we call the digital’ (Nash. 2017: 113). It is no secret again, that human life plays out on social media in a curated and semi-fictional fashion; where platforms are built to endorse this cultural reproduction, and exist naturally as an accessory to certain capitalist ideals through the blurring of lines between life and advertising.

Figure 12

We share our aesthetic experiences of the real world online; but naturally, these experiences are reduced to the mere amateur visualisation of the real world. We cannot experience the reality pictured, just the photograph of the real. Aesthetic experience of the everyday exists in art, online and the physical realm; great artworks such as Rinko Kawauchi’s pieces capture this ‘sensuous and imaginative dimension of aesthetic experience’ (Leddy in Light and Smith. 2005: 7). Even through the barrier of photography; we experience the everyday aesthetics of place and humanity in Kawauchi’s work; rather than the photograph itself.

Figure 13

Returning to Kessels’ ‘24hrs in Photos’, here we see private imagery becoming public imagery; and at the same time becoming what we consider to be art. It mimics this same experience an image goes through when uploaded and shared to Instagram. Where, human experience no longer remains private; moving slowly into a public void, and suddenly exposing our lives and identity to a space where ‘someone is nearly always watching and recording’ (Mirzoeff. 1999: 2). It is this blurred region where imagery never considered art suddenly becomes art; because it is declared to be art in a location that denotes it to be so (Tromoel. 2013: 10).

Again, Kessels’ ‘24hrs in Photos’ reminds us of the everyday aesthetics of human experience that play out in private spaces, online and in art; ‘art and aesthetics are directly plugged into the electric waves of life’ (Goriunova. 2012: 18).

Figure 14

In this documentation of the installation of ‘24hrs in photos’ is exhibited in a religious space, discussing not only the way we digest imagery on the internet daily; but also the void religion finds itself in after consumerism and in modern, daily life. The images of private and personal human experience draw a parallel to the empty space; revealing to me this concept of emptiness in religious buildings of worship; that individuals now worship their own lives to share to the world via social media. The work looks towards the future of photography together with the future of humanity; displaying this all consuming obsession with ourselves, our aesthetic nature and finally our culture. This is integral to our current understanding of human existence in the digital age; ‘the simultaneous domestication of photography and aestheticization of everyday life (...) are also found in the architectures and affordances of Instagram’ (MacDowall and De Souza. 2017: 9).

List of Figures:

Figure 1: AL-ARASHI, Yumna. 2014. ‘Northern Yemen’. From Yumna Al-Arashi [online]. Available at: https://yumnaaa.com/NORTHERN-YEMEN

Figure 2: ULMAN, Amalia. 2014. ‘Excellences & Perfections’. From Instagram: @amaliaulman [online]. Available at: https://instagram.com/amaliaulman?igshid=txj4d7sby8jr

Figure 3: ULMAN, Amalia. 2014. ‘Excellences & Perfections’. From Instagram: @amaliaulman [online]. Available at: https://instagram.com/amaliaulman?igshid=txj4d7sby8jr

Figure 4: ULMAN, Amalia. 2014. ‘Excellences & Perfections’. From Instagram: @amaliaulman [online]. Available at: https://instagram.com/amaliaulman?igshid=txj4d7sby8jr

Figure 5: KAWAUCHI, Rinko. 2001. ‘Utatane’. From Rinko Kawauchi [online]. Available at: http://rinkokawauchi.com/en/works/284/

Figure 6: KAWAUCHI, Rinko. 2011. ‘Illuminance’. From Rinko Kawauchi [online]. Available at: http://rinkokawauchi.com/en/works/194/

Figure 7: ULMAN, Amalia. 2014. ‘Excellences & Perfections’. From Instagram: @amaliaulman [online]. Available at: https://instagram.com/amaliaulman?igshid=txj4d7sby8jr

Figure 8:KESSELS, Erik. 2011. ‘24 Hrs in Photos’. From Erik Kessels [online]. Available at: https://www.erikkessels.com/24hrs-in-photos

Figure 9: KESSELS, Erik. 2011. ‘24 Hrs in Photos’. From Erik Kessels [online]. Available at: https://www.erikkessels.com/24hrs-in-photos

Figure 10: KAWAUCHI, Rinko. 2005. ‘The Eyes, The Ears’. From Rinko Kawauchi [online]. Available at: http://rinkokawauchi.com/en/

Figure 11: KAWAUCHI, Rinko. 2001. ‘Utatane’. From Rinko Kawauchi [online]. Available at: http://rinkokawauchi.com/en/

Figure 12: KAWAUCHI, Rinko. 2011. ‘Illuminance’. From Rinko Kawauchi [online]. Available at: http://rinkokawauchi.com/en/

Figure 13: KESSELS, Erik. 2011. ‘24 hrs in Photos’. From Erik Kessels [online]. Available at: https://www.erikkessels.com/24hrs-in-photos

Figure 14: KESSELS, Erik. 2011. ‘24 hrs in Photos’. From Erik Kessels [online]. Available at: https://www.erikkessels.com/24hrs-in-photos

Bibliography:

GORIUNOVA, Olga. 2012. Art Platforms and Cultural Production on the Internet. New York: Routledge.

KESSELS, Erik. ca. 2020. ‘24 Hrs In Photos’. Erik Kessels [online]. Available at: https://www.erikkessels.com/24hrs-in-photos [accessed 06 October 2020] MACDOWALL, Lachlan John and Poppy DE SOUZA. 2017. “I’d Double Tap That!!”: Street Art, Graffiti, and Instagram Research’. Media, culture & society 40 (1), 3-22.

MIRZOEFF, Nicholas. 1999. An Introduction to Visual Culture. London: Routledge. NASH, Adam. 2017. ‘Art Imitates the Digital’. Lumina (Juiz de Fora, Brazil) 11(2), 110-25. NEW YORK TIMES EVENTS. 2017. ‘NYT Art for tomorrow 2017: The Instant Image for the Global Audience’ [Panel Discussion]. Available at:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KNIQnEbve5Q [accessed 30 September] READ, Herbert. 1963. To Hell with Culture and Other Essays on Art and Society. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

SAITO, Yuriko. 2019. ‘Aesthetics of the Everyday’. The Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy (Winter 2019 Edition) [online]. Available at:

https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2019/entries/aesthetics-of-everyday [accessed 27 October 2020]

SHIMADA, Naomi and Sarah RAPHAEL. 2019. Mixed Feelings: Exploring the Emotional Impact of Our Digital Habits. London: Quadrille.

SMITH, Johnathon M and Andrew LIGHT. 2005. The Aesthetics of Everyday Life. New York; Chichester, West Sussex: Columbia University Press.

TROEMEL, Brad and Brad TROEMEL. 2013. ‘Art after Social Media.’ Art Papers 37(4), [online], 10–5. Available at: http://search.proquest.com/docview/1467633110/.